Some planets in other solar systems orbit so close to their stars that they are spiral inward, ultimately to be ripped apart and eaten by their stars.

Looking for signs of that in-spiral, many astronomers, including students in my own research group, study transit signals — the shadows of planets as they pass in front of their host stars, as seen from Earth. For a planet spiral into its star, the time between one transit and the next will get shorter and shorter over many years. And so by measuring many transits, we can find signs of tidal in-spiral.

One big problem with looking for such tidally-driven signals is that other effects can also effect the time between transits, and so we need a good way to distinguish between these different effects.

In a recent paper from our group, we map out some ways to tell the difference between these different effects using tides. The bottom line: it’s not easy to tell the difference, but observations of exoplanet transits by citizen scientists can be a really important tool for the long-term monitoring required to find tidally decaying worlds that are not long for this world.

Related Publications

- “Metrics for Optimizing Searches for Orbital Precession and Tidal Decay via Transit Timing and Occultation Timing.” (2026). The Astronomical Journal, Volume 171, Number 2.

- “Doomed Worlds. I. No New Evidence for Orbital Decay in a Long-term Survey of 43 Ultrahot Jupiters.” (2024). The Planetary Science Journal, Volume 5, Number 7.

- “Metrics for Optimizing Searches for Tidally Decaying Exoplanets.” (2023). The Astronomical Journal, Volume 166, Number 4.

The distribution of orbital eccentricities e of extrasolar planets with semimajor axes a > 0.2 AU is very uniform, and values for e are relatively large, averaging 0.3 and broadly distributed up to near 1. For a < 0.2 AU, eccentricities are much smaller (most e < 0.2), a characteristic widely attributed to damping by tides after the planets formed and the protoplanetary gas disk dissipated. Most previous estimates of the tidal damping considered the tides raised on the planets, but ignored the tides raised on the stars. Perhaps most important, in many studies the strongly coupled evolution between e and a was ignored. In Jackson+ (2008a), my colleagues and I modeled the coupled tidal evolution of e and a for many extrasolar planets and confirmed that even close-in planets probably began with broadly distributed e-values, like those for planets far from their host stars and unaffected by tides. The accompanying evolution of a-values showed most close-in planets had significantly larger a at the start of tidal migration, and the current small values of a were only reached gradually due to tides over the ages of the planets.

Related Scientific Publications:

- Jackson+ (2008a). “Tidal Evolution of Close-in Extrasolar Planets.” ApJ 678, 1396.

- Jackson+ (2008). “Tidal evolution of close-in extra-solar planets.” Proceed. IAU 249, 187.

Extrasolar gas giant planets close to their host stars have likely undergone significant tidal evolution since the time of their formation. Tides probably dominated their orbital evolution once the dust and gas cleared away, and as the orbits evolved there was substantial tidal heating within the planets. The tidal heating history of each gas giant may have contributed significantly to the thermal budget governing the planet’s physical properties, including its radius, which in many cases may be measured by observing transit events. Typically, tidal heating increases as a planet moves inward toward its star and then decreases as its orbit circularizes. In Jackson+ (2008b), my colleagues and I computed tidal heating histories for several planets with measured radii. Several planets, including, for example, HD 209458 b, may have undergone substantial tidal heating during the past billion years, perhaps enough to explain its large measured radius. Our models also show that GJ 876 d may have experienced tremendous heating and is probably not a solid, rocky planet.

Tidal heating of rocky (or terrestrial) extrasolar planets may also span a wide range of values, depending on stellar masses and the planets’ initial orbits. Tidal heating may be sufficiently large (in many cases, in excess of radiogenic heating) and long-lived to drive plate tectonics, similar to the Earth’s, which may enhance the planet’s habitability. In other cases, excessive tidal heating may result in violent volcanism as for Jupiter’s moon Io, probably rendering them unsuitable for life. On water-rich planets, tidal heating may generate subsurface oceans analogous to the ocean in Jupiter’s moon Europa, with similar prospects for habitability. Tidal heating may enhance the outgassing of volatiles, contributing to the formation and replenishment of a planet’s atmosphere. In Jackson+ (2008c), my colleagues and I modeled the tidal heating and evolution of hypothetical extrasolar terrestrial planets to investigate the influence on planetary habitability.

Related Press:

- Tides Have Major Impact on Planet Habitability – U of AZ press release

- Talking About Tides – podcast interview with Simon Mitton about tides and planetary habitability

Related Scientific Publications:

- Jackson+ (2008c). “Tidal Heating of Extrasolar Planets.” ApJ 681, 1631.

- Jackson+ (2008b). “Tidal heating of terrestrial extrasolar planets and implications for their habitability.” MNRAS 391, 237.

- Jackson+ (2008). “Tidal Heating of Extrasolar Terrestrial-scale Planets and Constraints on Habitability.” BAAS 40, 391.

The distribution of the orbits of close-in exoplanets shows evidence for ongoing removal and destruction by tides. Tides raised on a planet’s host star cause the planet’s orbit to decay, even after the orbital eccentricity has dropped to zero. Comparison of the observed orbital distribution and predictions of tidal theory shows good qualitative agreement, suggesting tidal destruction of close-in exoplanets is common. The process can explain the observed cutoff in small orbital semimajor axis values, the clustering of orbital periods near three days, and the relative youth of transiting planets. Contrary to previous considerations, a mechanism to stop the inward migration of close-in planets at their current orbits is not necessarily required. Planets nearing tidal destruction may be found with extremely small semimajor axes, possibly already stripped of any gaseous envelope. The recently discovered CoroT-7 b may be an example of such a planet and will probably be destroyed by tides within the next few Gyrs. Also, where one or more planets have already been accreted, a star may exhibit an unusual composition and/or spin rate.

Related Press:

Press release from University of Washington about tidal destruction of planets- Missing Planets Attest To Destructive Power Of Stars’ Tides – Science Daily

Related Scientific Publications:

- Jackson+ (2009). “Observational Evidence for Tidal Destruction of Exoplanets.” ApJ 698, 1357.

CoRoT-7 b was the first confirmed rocky exoplanet and was discovered by the CoRoT mission, but, with an orbital from its host star of only 0.0172 AU (100 times closer than the Earth is to the Sun), its origins may be unlike any rocky planet in our Solar system. In Jackson+ (2010), my colleagues and I considered the roles of tidal evolution and atmospheric mass loss in CoRoT-7 b’s history, which together have modified the planet’s mass and orbit. If CoRoT-7 b has always been a rocky body, evaporation may have driven off almost half its original mass, but the mass loss may depend sensitively on the extent of tidal decay of its orbit. As tides caused CoRoT-7 b’s orbit to decay, they brought the planet closer to its host star, thereby enhancing the mass loss rate. Such a large mass loss also suggests the possibility that CoRoT-7 b began as a gas giant planet and had its original atmosphere completely evaporated. In this case, we found that CoRoT-7 b’s original mass probably did not exceed 200 Earth masses (about two-third of a Jupiter mass). Tides raised on the host star by the planet may have significantly reduced the orbital semimajor axis, perhaps causing the planet to migrate through mean-motion resonances with the other planet in the system, CoRoT-7 c. The coupling between tidal evolution and mass loss may be important not only for CoRoT-7 b but also for other close-in exoplanets, and future studies of mass loss and orbital evolution may provide insight into the origin and fate of close-in planets, both rocky and gaseous.

Related Press:

Related Scientific Publications:

- Jackson+ (2010). “The roles of tidal evolution and evaporative mass loss in the origin of CoRoT-7 b.” MNRAS 407, 910.

- Jackson+ (2010). “Is CoRoT-7 B the Remnant Core of an Evaporated Gas Giant?” BAAS 42, 444.

For a massive (Jupiter-sized) planet orbiting very close to its host star, the planet’s gravity can distort the shape of the star, similar to the tides raised in the Earth’s oceans by the Moon’s gravity. As these stellar tidal waves flow on the star in response to the planet’s gravity, the star can appear to brighten and dim slightly. The tides are VERY small (about 100 meters tall), and so the amount of brightening and dimming is very small, tens of parts per million, and looking for this astronomical signal is like looking for a firefly against the glare of football stadium lights. The figure below illustrates the effect.

My colleagues and I created a new model for Ellipsoidal Variations Induced by a Low-Mass Companion, the EVIL-MC model, and in Jackson+ (2012), we used the EVIL-MC model to analyze observations from the Kepler mission of the HAT-P-7 system, an F-type star orbited by a roughly Jupiter-mass gas giant companion in a 2-day orbital period. Our analysis allowed us to estimate the planet’s mass and the (blackbody) temperature of the planet’s dayside, at about 2680 K. We also found a large difference between the day- and nightside planetary flux, with little nightside emission, which is qualitatively consistent with little day-to-night atmospheric circulation and in-line with other observations of very hot gas giants very close to their host stars.

Related Scientific Publications:

- Jackson+ (2012). “The EVIL-MC Model for Ellipsoidal Variations of Planet-hosting Stars and Applications to the HAT-P-7 System.” ApJ 751, 112.

- Jackson & Carlberg (2012). “Ellipsoidal Variation Analysis of Kepler Observations Using the EVIL-MC Model.” DPS Meeting.

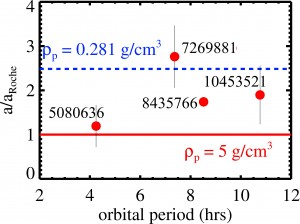

I recently led a search for very short-period transiting objects in the publicly available Kepler dataset, and this preliminary survey has revealed thirteen four planetary candidates, with periods ranging from 3.3 to 10 4 to 11 hours. I analyzed the data for these candidates using models that include transit light curves, ellipsoidal variations, and secondary eclipses, to constrain the candidates’ radii, masses, and effective temperatures. Even with masses of only a few Earth masses, the candidates’ short periods mean they may induce stellar radial velocity signals (~ 10 m/s), detectable by currently operating facilities. The origins of such short-period planets are unclear, but it’s possible that they are the remnants of disrupted hot Jupiters. If confirmed, these candidates would be some of the shortest-period planets ever discovered, and if common, such planets would be particularly amenable to discovery by the planned TESS mission, which is specifically designed to find short-period rocky planets.

Related press:

- Time Really Flies on These Kepler Planets.

- Razor’s edge — New class of exoplanets clock orbits as short as 3 hours

- Super-Fast Alien Planets May Be Skimming the Surface of Their Stars

Related scientific publications:

- Jackson+ (2013). “A Survey for Very Short-Period Planets in the Kepler Data.” arxiv 1308.1379.

- Jackson (2013). “Looking for Very Short-Period Planets with Re-Purposed Kepler.” arXiv 1309.1499.