In 1986, superstars Lionel Richie and Michael Jackson won a Grammy for “Best Song of the Year” for “We are the World“, a single recorded to support the African charity USA for Africa (https://usaforafrica.org/) to provide food and relief aid to starving people in Africa, specifically Ethiopia where a famine raged. With sales in excess of 20 million copies, it is the eighth-bestselling physical single of all time, and it immediately generated 60 million dollars.

But 1986 also marked the 300th anniversary of one of the most popular science books of all time, Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds. And a NASA mission just over the horizon may turn the sci-fi conversations about alien life from this classic pop-sci book into science fact.

I Want to Know What Above Is

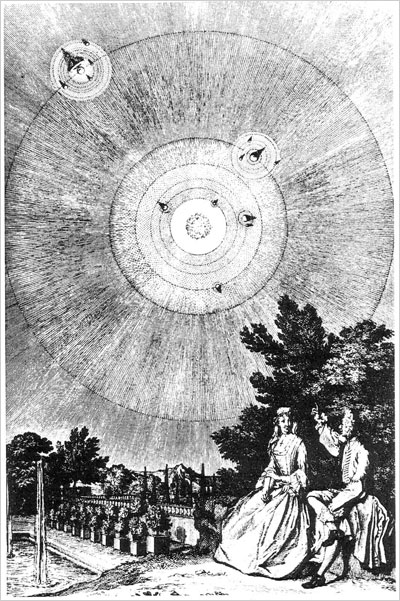

Published in 1686 (around the same time that New York City was granted its first charter in the Americas) Conversations was one of the first works to popularize ideas about alien life. Written by the French natural philosopher Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle, Conversations provides a sweeping and accessible survey of the then recent discoveries and speculations by early Enlightenment thinkers like Descartes and Copernicus.

The book, written in French to broaden its popular appeal, is framed as a series of conversations between an unnamed natural philosopher (an obvious stand-in for Fontelle himself) and an inquisitive Marquise. Under the darkening twilight sky, the philosopher and Marquise discuss the natures of the alien lifeforms assumed to inhabit the Solar System and worlds beyond.

Simplistic but impressively insightful ideas inform their speculations. Pointing out that, being much closer to the Sun than Earth, the philosopher explains that Mercury must experience much higher temperatures:

But what must the inhabitants of Mercury be? We are above twice the distance from the sun that they are. They must be almost mad with vivacity.

Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds, Grunning’s 1803 English translation

And what about the worlds more distant from the Sun? Fontenelle, in the guise of his anonymous philospher, points out that Saturn takes 30 years to circle the Sun, while Earth takes one. Thus, like extraterrestrial Ents, Saturnians deliberate more slowly than frenetic Earthlings:

Then, replied she, the people are very wise in Saturn, for you told me they were all mad in Mercury.

If they are not very wise, answered I, they are at least, I suppose, very phlegmatic. Their features could not accommodate themselves to a smile; they require a day’s consideration before they answer any question…

Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds, Grunning’s 1803 English translation

The book’s conversational style, approachable analogies (and mildly suggestive setting) won it wild popularity. Although subject to occasional religious restrictions, Conversations was still being translated into new languages more than one hundred years after its initial publication.

The Power of Thuds

Although understanding of science and the requirements for life was extremely limited in the 17th century (Newton’s Principia wasn’t even published until the year after Conversations), Fontenelle hit on some of the key considerations when it comes to what makes a world suitable for life. The dependence of a planet’s temperature on its distance from its host star lies at the heart of the habitable zone, the region around a star in which an Earth-like planet could have Earth-like temperatures.

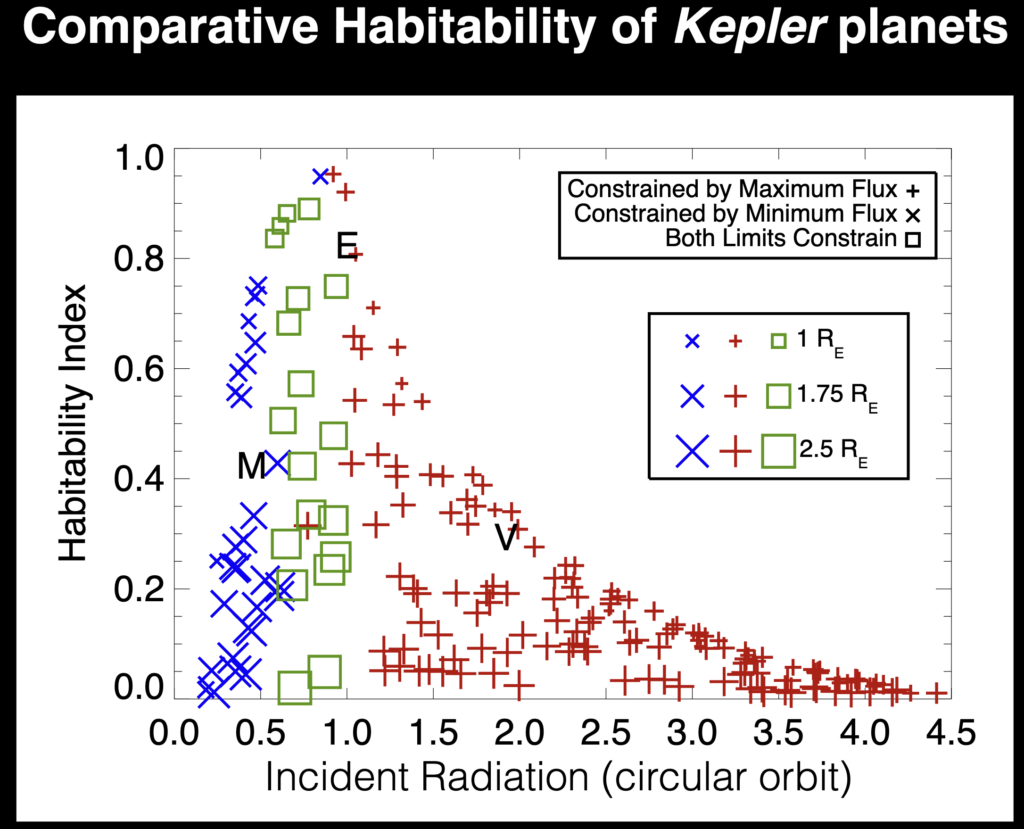

Indeed, scientists have developed a variety of ways to decide how likely a distant world is to be able to host life, including the habitability index. Combining several factors related to the host star brightness and the planet’s size and orbit, the habitability index attempts to gauge which planets might have climates most like the Earth’s

Credits: NASA/SOFIA/L. Cook/L. Proudfit

But, of course, climate is not the only thing that determines whether a planet has life or not. Making life requires the right ingredients, and, for the Earth, much of the required chemicals were delivered by asteroids and comets. Most of our water, for example, probably originated from comets thudding into the Earth’s surface billions of years ago.

But water is not the only chemical required for life. Other chemicals, like carbon, nitrogen, even phosphorous, are essential ingredients in life’s building blocks. Delivering those chemicals via impactor to the earth Earth’s oceans was easy as dropping a stone in a pond. But what if you’re a world on which all your life-giving water is sheltered from space behind a solid wall of ice?

Science for Nothing (and Life-Checks for Free)

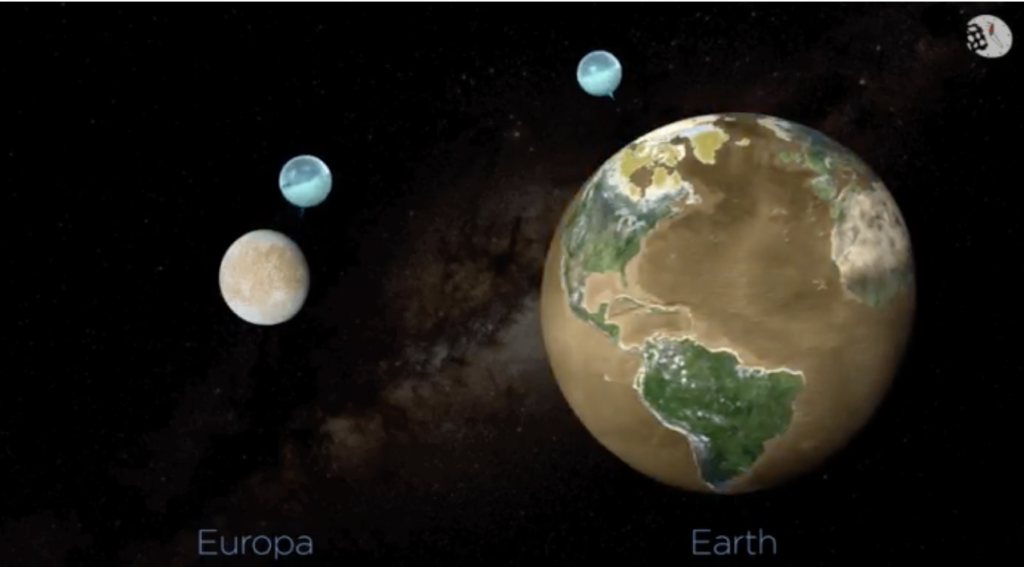

On the surface, Jupiter’s moon Europa seems like a great place for life to get a foothold. An ice-rich moon, Europa hosts a global ocean with as much liquid water as the Earth has.

But all that life-giving water lies beneath Europa’s icy surface, and whether that ice shell is miles thick or just a thin veneer remains a mystery. If Europa’s shell really is miles thick, then the ingredients necessary for life that rained down on the Earth billions of years ago may be locked outside, prevented from seeding the expansive Europan seas. But new evidence suggests that Europa’s shell might actually be paper-thin.

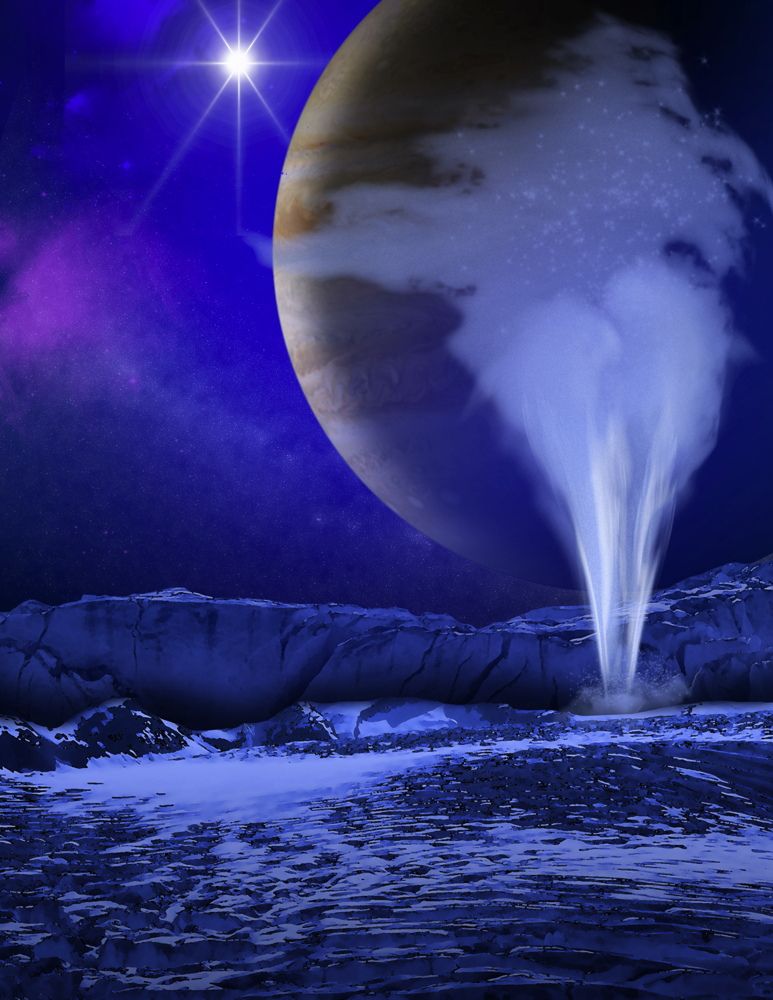

Hubble observations collected in 2019 showed that, bursting forth from beneath Europa’s crust, water spouts were spraying into space. These geysers, powered by tidal heating, show that Europa’s oceans must not lie too deep beneath the icy crust, and so impactors that might deliver life-giving chemicals may be able to periodically break the ice and seed the oceans.

Whether this discovery means Europa’s oceans are bursting with life or just slushy deserts remains to be seen. But NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, slated to visit Europa in 2030, will provide strong evidence one way or another.

And for Clipper, the geysers may be an easy way to sample the otherwise difficult-to-probe oceans. By spewing the ocean contents into space, the geysers will provide a taste of the ocean chemistry, and Clipper will include a high-precision spectrometer just for this purpose.

Want to learn more about life’s chemical story? Join Boise State Physics for our First Friday Astronomy event on Fri, Sep 2 at 7:30p MT when we will host University of South Florida’s Prof. Matthew Pasek. Attend in-person (https://maps.boisestate.edu/?id=715#!m/89075) or virtually (boi.st/astrobroncoslive).