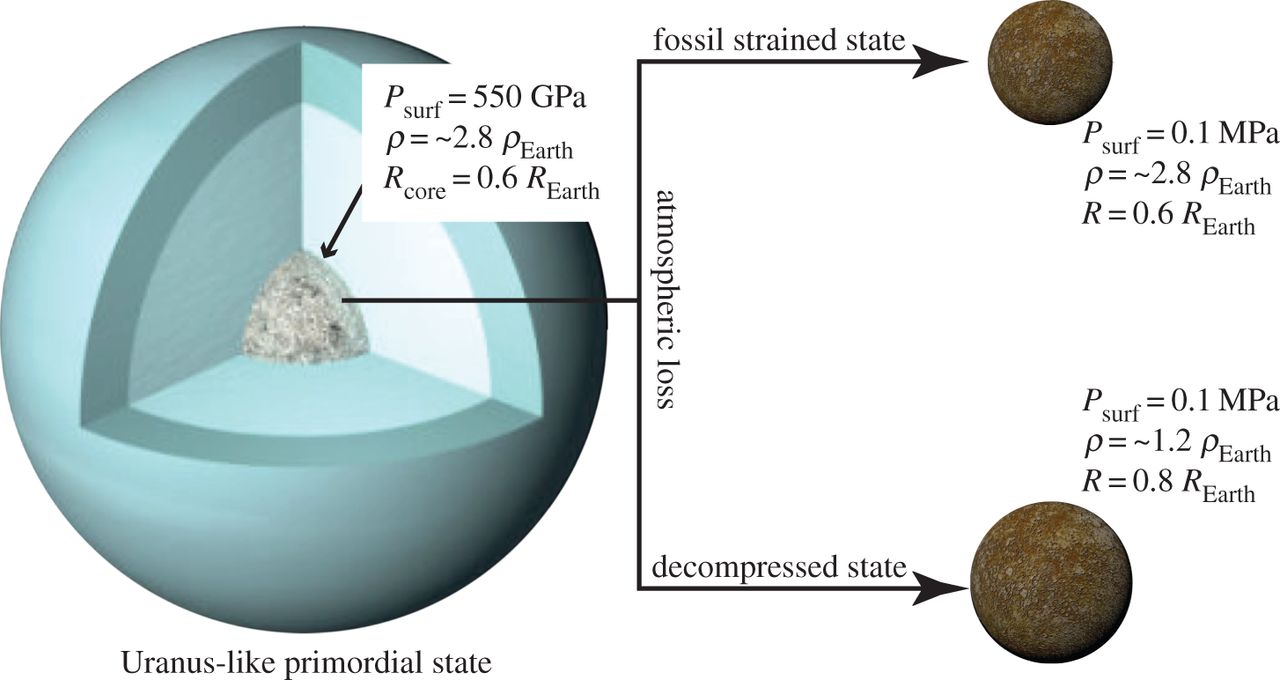

Figure from Mocquet et al. (2014) show how a gaseous planet might evolve into a dense, rocky core.

Another blast from the past, Mocquet et al. (2014) was the topic of our journal club this week, a paper that seeks to answer the question “What would Jupiter look like if you took away its atmosphere?”.

Given the enormous number of gas-rich exoplanets very close to their host stars discovered in recent years, many astronomers (including myself) have wondered whether such planets could have their atmospheres completely removed.

We certainly see some very hot planets where intense sunlight is blasting away their atmospheres, and in other cases, the star’s gravity can rip off the atmosphere. And so it’s not crazy to think some gaseous planets might completely lose their atmospheres.

Would anything be left over? Astronomers think that gas giants like Jupiter are like big cherries, with a squishy outer layer of gas wrapped around a dense pit of rock. Indeed, the Juno mission currently in orbit around Jupiter is designed to measure the size of Jupiter’s core by measuring its gravitational field very precisely.

And so the cores of gas giants are under enormous pressure – for instance, the core of Jupiter is being squeezed by 45,000 times the pressure at the bottom of the Mariana Trench on Earth.

In their study, Mocquet and colleagues explore what happens to a rocky core under such large pressures. Not surprisingly, they find that such a core would have an enormous density, perhaps three times larger than the Earth’s.

But what is surprisingly is that their results suggest the core might retain a very large density even if you removed the overlying atmosphere. It’s as if you squeezed down a nerf ball and then let it go – instead of springing back immediately, the nerf ball would take a few billion years to decompress. This means that we might be able to identify the cores of former gas giants by looking for planets roughly the size of Earth but with anomalously high densities.

And in fact, such planets have been found – the planet Kepler-57 b has a mass more than 100 times Earth’s but squeezed into a volume only ten times larger, giving a density of almost 44 grams per cubic centimeter – twice the density of the densest element on Earth, osmium.

So in their search for fossils, gas giant paleontologists should keep in mind that the bones of extinct gas giants may have distinctively large densities, almost as dense as adamantium.