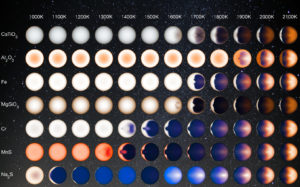

What hot Jupiters might look like for a range of atmospheric temperatures. From http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/spaceimages/details.php?id=PIA21074.

Second day of DPS, and I enjoyed several fascinating sessions on exoplanet atmospheres. One of the most visually appealing talks was given by Vivian Parmentier, a planetary scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Lab.

Parmentier talked about clouds in the atmospheres of hot Jupiters, gas giant planets similar in composition and structure to Jupiter but much closer to their host stars than Mercury is to our Sun. Because they’re so close to their stars, hot Jupiters are … well … very hot, with temperatures reaching thousands of degrees.

These very high temperatures probably mean that the atmospheres contain clouds made of some exotic condensables, such as iron, cromium, or even ruby.

In his talk, Parmentier explained that understanding what kinds of clouds might form in these atmospheres is important for interpreting the growing collection of spectra collected using the Hubble and Spitzer Space Telescopes. He also showed a beautiful photo album, realistically depicting the appearances of hot Jupiters for a range of atmospheric conditions.

A detailed, if nuanced, story is emerging from these data, suggesting hot Jupiters have highly dynamic meteorology with chemically complex clouds.

I attended the Women in Planetary Science Discussion Hour, at which we addressed several issues confronting the planetary science community when it comes to expanding diversity in the field. Several planetary scientists have conducted recent studies revealing the current state of the field (e.g., the fraction of women involved in space missions has not kept pace with the fraction of women in planetary science overall).

These studies have also pointed out ways to expand our pool of talented scientists, including ways to improve faculty searches to make sure the people standing at the front of the classroom resemble more closely the people sitting behind the desks. The Women in Planetary Science blog gives a lot of relevant resources.