Titan

All posts tagged Titan

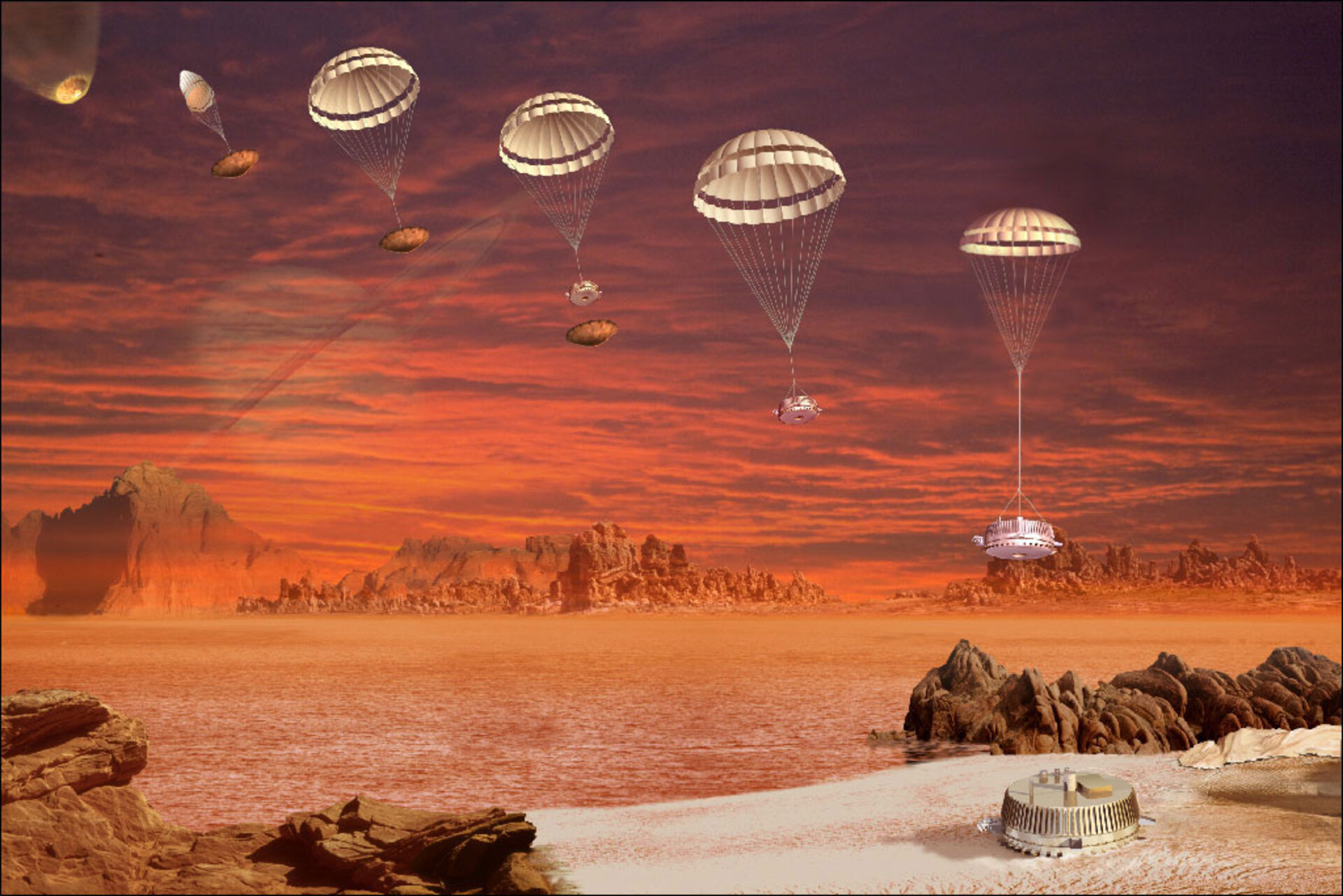

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, was discovered by the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens in 1655, the same year courts in Virginia first ruled slavery was legal in the American colonies. It took another 350 years before humans visited Titan upclose, leaving this, the largest moon in the Solar System, an object of wonder and speculation. But even after many years of intimate study, Titan remains enshrouded, both figuratively and literally. Its secrets may persist until NASA’s Dragonfly mission visits the world again in 2034, and if history is any guide, probably long after too.

Continue Reading

Arguably the best animé of all time, “Cowboy Bebop” is set in a not-too-distant future, when humans inhabit planets and moons across the solar system. In fact, one of the moon inhabited, Saturn’s moon Titan, features as the site of a violent, Desert Storm-like battle among sand dunes and scorpions.

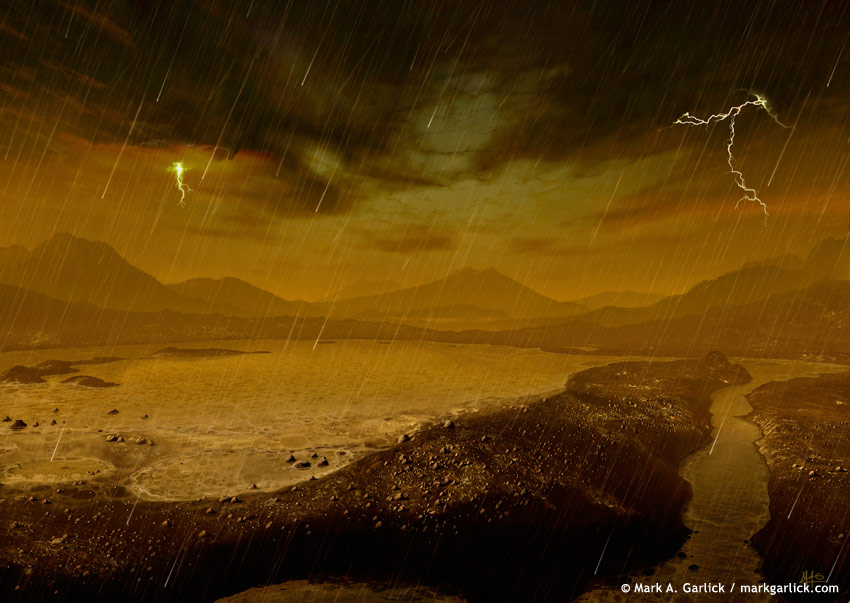

“Cowboy Bebop” aired in Japan in 1998-1999, about a year after NASA launched the Cassini-Huygens mission to explore the Saturn system, including Titan. Shortly after arriving at Saturn, Cassini began collecting infrared observations of Titan, allowing scientists to peer through Titan’s hazy atmosphere. They found a surprisingly Earth-like world — violent but irregular storms (albeit of methane and ethane) and vast seas (primarily confined to the poles).

Scientists also found expansive dune fields girding the equator. Unlike terrestrial dunes, which are made mostly from silicate grains, these dunes were made (somehow) from carbon- and ice-rich particles. And an even more recent analysis of Cassini observations shows that Titan has something else in common with Earth: large dust storms.

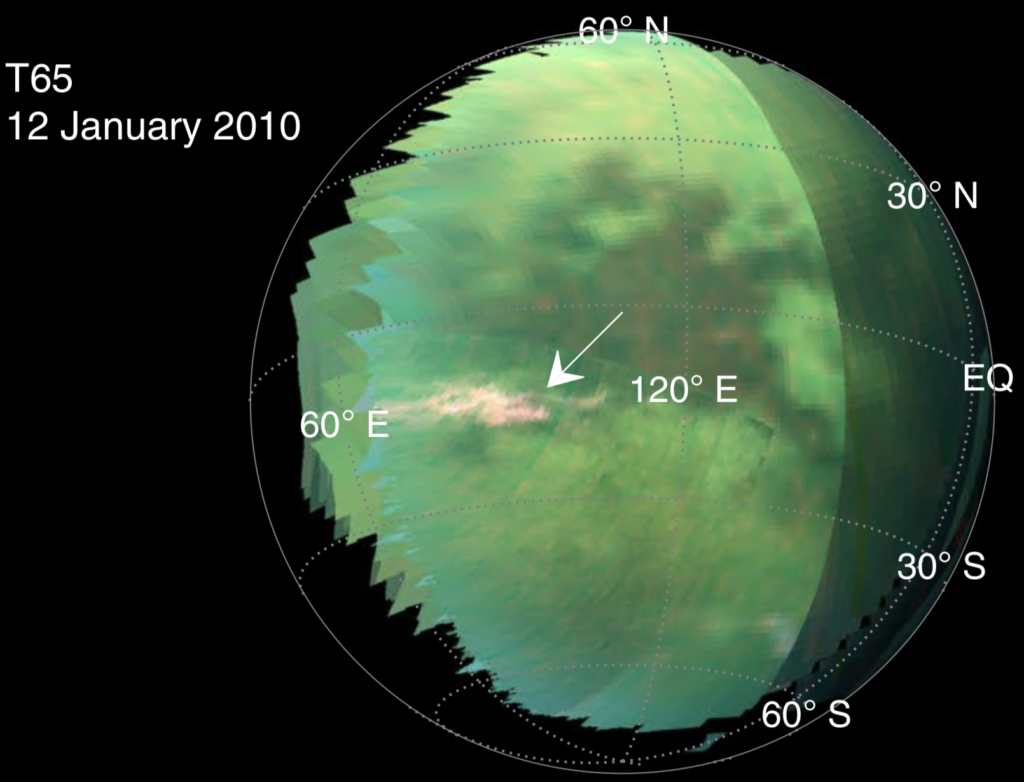

In their study from late last year, Sébastien Rodriguez, an astronomer at the University Paris Diderot, and co-authors looked at maps of Titan collected by Cassini’s VIMS instrument and found that, over the dune regions, a large bright feature appeared and disappeared several times over the course of a few weeks.

Now, just because there is a bright spot on Titan that changes with time does NOT mean it has to be a dust storm, but Rodriguez and colleagues go to great lengths to show that other explanations don’t fit.

For instance, previous observations of Titan found equatorial clouds that produced downpours of methane and ethane on the surface. Superficially, these clouds resembled Rodriguez’s putative dust storms.

But Rodriguez’s dust clouds can only be seen in the few wavelengths of infrared light that are known to penetrate Titan’s atmosphere all the way to the ground. Storm clouds can be seen even in wavelengths that don’t reach the ground since they ascend high into the atmosphere.

Rodriguez and colleagues are even able to estimate the size of the dust grains — the dust clouds are much easier to see at 5 micron-wavelengths than at the shorter wavelengths that also probe to Titan’s surface. That probably means the grains are about 5 microns.

If Titan’s dust really is that small, it’s much smaller than sand grains and even smaller than the dust we usually see on Earth. It turns out that the aerodynamic behavior of a wind-blown particle depends, among other things, on its size. For a planet with a given atmospheric density, winds are good at blowing particles of a specific size — too small and the particles stick together; too big and the wind can’t lift the particles.

Rodriguez and colleagues estimate that windspeeds of about 3+ meters per second (about 7 miles per hour) would required to loft 5-micron dust grains on Titan. That may seem small, but the winds measured by the Huygens probe during its descent onto Titan measured even weaker near-surface winds of less than 2 meters per second.

However, the study’s authors point that stronger winds probably accompany Titanian rain storms. If such a storm had just taken place before they spotted the dust cloud, that could easily explain how the dust was lofted.

Ultimately, answering the question of Titan’s dust storms will require visiting the world again. Fortunately, NASA is investigating sending an automated drone to fly the Titanian skies, the Dragonfly mission, back to Titan in 2025. Whether that mission flies or not will be decided later this year.

I’m sitting in the hotel lobby at the Woodlands Marriott, waiting for my supershuttle to IAH and recouperating from my second Lunar and Planetary Sciences Conference, LPSC. Before I’m whisked away back to Boise, I thought to write about a few of the fascinating and mind-blowing things I saw this week.

First of all, LPSC is an annual conference that focuses on the geology, geochemistry, and geophysics of planetary science. There’s a lot of focus on solar system bodies with solid surfaces, as opposed to the annual DPS meeting, which has a bit broader focus.

I arrived on Sunday evening and dove immediately in, helping with the First-Timers’ presentation review, an opportunity for new-comers to the meeting to have more senior folks provide feedback on their posters or oral presentations.

Monday dawned cloudy, and I sat through several talks about our sister planet Mars. One that stuck out for me was one about field experiments to explain the perennially mysterious gully formations found on martian slopes with sleds of dry ice.

Tuesday saw me in a session on Saturn’s moon Titan, a cornucopia of geology and atmospheric physics. One particularly impressive talk discussed work to understand how methane deluges on Titan modified the surface.

Titan-Farnsworth: Analyzing spectral properties of regions that just received methane rain on Titan #LPSC2018 pic.twitter.com/YubU1Z9Hq9

— Brian Jackson (@decaelus) March 20, 2018

Tuesday evening, I presented our group’s work flying drones through active dust devils.

Wednesday was packed with talks on sediment transport experiments and analyses, attempting to decipher the martian aeolian cycle, including a neat study of time-lapse imagery of martian dunes.

Aeolian Geo-Chojnacki: Beautiful animations of mobile dunes seen on Mars @HiRISE #lpsc2018 pic.twitter.com/q6kIV1aGHb

— Brian Jackson (@decaelus) March 21, 2018

Thursday was packed with Pluto and results from New Horizons. One talk that stuck in my mind was an analysis of landslides on Pluto’s moon Charon, which, frankly, was a little bit of a tear-jerker. Hard to believe that not one hundred years ago, we didn’t even know Pluto existed. Now we’re trying to understand the system’s geology.

Pluto-Beddingfield: Landslides on Charon were low-friction and low enough energy that the ice probably did not melt in falling #lpsc2018 pic.twitter.com/MVaZ8U7nz4

— Brian Jackson (@decaelus) March 22, 2018

Friday morning wrapped up the meeting with a series of talks about glacial geology on Mars, including a fabulous presentation on mysterious geomorphic features on Mars. Even though these features look for all the world like glacial flow, they appear on totally flat ground, where flow shouldn’t be possible.

Glacial Mars-@Shann0nMars: Strange flow-like features in valleys might represent ancient glacial flows #lpsc2018 pic.twitter.com/u721TzFN0c

— Brian Jackson (@decaelus) March 23, 2018

And now to catch the shuttle.