Hot Jupiters are gas giant planets like Jupiter but orbiting so close to their host stars that they can be as hot as small stars. In fact, some suffer such strong irradiation that their atmospheres are being blasted off into space. These objects were among the first exoplanets detected, and their origins and fates remain unclear.

Being so hot, their atmospheres are also unlike any planet’s in our solar system, but we can be certain that, with temperatures hot enough to vaporize rock, the weather on these planets is highly dynamic. The video below shows what happens to one such planet as it gets blast-roasted by its host star – a giant thermal wave screams around the planet.

Weather forecasts on hot Jupiters would to have keep track of super-sonic winds, ruby rain, and warm fronts heated by magnetic fields. And a recent study using observations from the Hubble Space Telescope shows that these dynamic atmospheres remain mysterious.

Led by Jacob Arcangeli of the University of Amsterdam, the study used the Wide-Field Camera onboard Hubble to watch WASP-18 as the hot Jupiter circled its star.

As the planet swings revolves around its star, we see first the cool nightside of the planet and then the blistering dayside. By measuring the diurnal cycle of infrared light emitted from the two sides of the planet, called the phase curve, Arcangeli and colleagues were able to measure their respective temperatures and learn something about the planet’s weather.

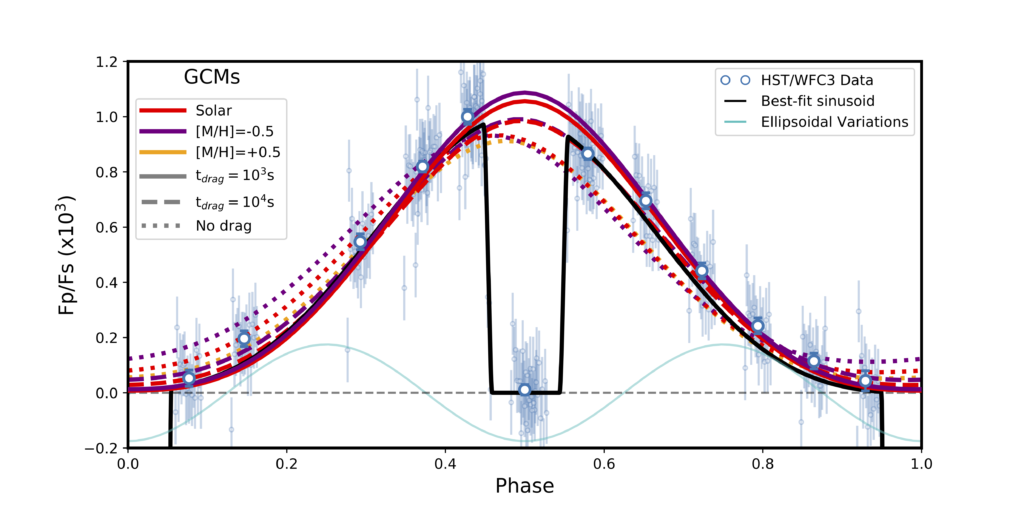

The figure above shows WASP-18b’s phase curve as blue points and a model fit to the data as a black line. By applying computer simulations for the planet’s weather, Arcangeli and colleagues estimated what they expected the phase curve to look like various assumptions about the planet’s composition and atmospheric dynamics.

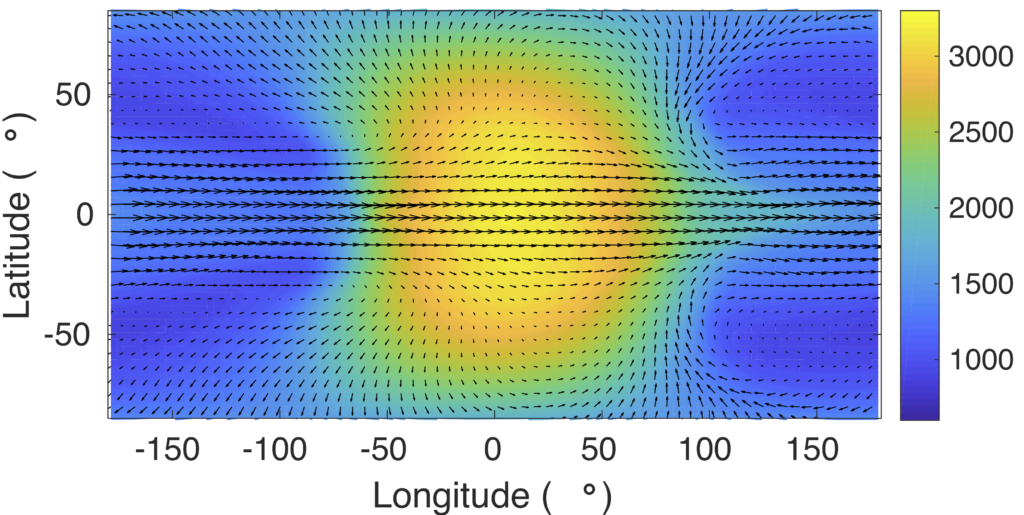

Using their models, they were able to draw a rough map of temperatures in WASP-18b’s atmosphere (shown above), like a weather map for the Earth. Like most hot Jupiters observed show far, the hottest place in WASP-18b’s atmosphere lies a little east of the point that receives the most sunlight, the substellar point. That’s because high windspeeds blow the strongly heated gas away toward the east, a little like the jet stream on Earth.

However, the winds inferred from the Hubble observations weren’t as strong as expected from the model, suggesting there is some form of drag or friction in WASP-18b’s atmosphere.

The likely culprit: the planet’s very own magnetic field. Gas in WASP-18b’s atmosphere is actually so hot, it can become somewhat plasma-fied, and plasma, consisting of hot charged particles, can interact with the hot Jupiter’s magnetic field.

This is totally unlike planets in our own solar system, where the atmospheres are comparatively cool and none of the gas has turned into plasma.

The upshot of this result is that we may be able to use observations of the meteorology on distant worlds to learn something about the planets’ magnetic fields, which originate deep inside the planet. So their weather may allow us to plumb the depths of these distant worlds.

First up was

First up was  This presentation was followed by

This presentation was followed by  Gupta described how the tilt of beds of sedimentary rock could be used to infer the presence of a river delta spilling out into the crater, which suggests the existence of a long-lived (millions of years) lake in the crater, probably billions of years ago

Gupta described how the tilt of beds of sedimentary rock could be used to infer the presence of a river delta spilling out into the crater, which suggests the existence of a long-lived (millions of years) lake in the crater, probably billions of years ago