Had a wonderful visit to London, Ontario last week, home of the University of Western Ontario. Weather wasn’t quite as nice as here in Boise, but the city was just as beautiful.

Had a wonderful visit to London, Ontario last week, home of the University of Western Ontario. Weather wasn’t quite as nice as here in Boise, but the city was just as beautiful.

My friend and colleague Catherine Neish arranged for me to give three talks while there — one on our crowd-funding effort, one on my exoplanet research, and one on our dust devil work.

I’ve posted two of the talks and abbreviated abstracts below. The dust devil talk, “Summoning Devils in the Desert”, is a reprise of a previous talk, so I didn’t include it below.

Crowdfunding To Support University Research and Public Outreach

In this presentation, I discussed my own crowdfunding project to support the rehabilitation of Boise State’s on-campus observatory. As the first project launched on PonyUp, it was an enormous success — we met our original donation goal of $8k just two weeks into the four-week campaign and so upped the goal to $10k, which we achieved two weeks later. In addition to the very gratifying monetary support of the broader Boise community, we received personal stories from many of our donors about their connections to Boise State and the observatory. I’ll talk about our approach to social and traditional media platforms and discuss how we leveraged an unlikely cosmic syzygy to boost the campaign.

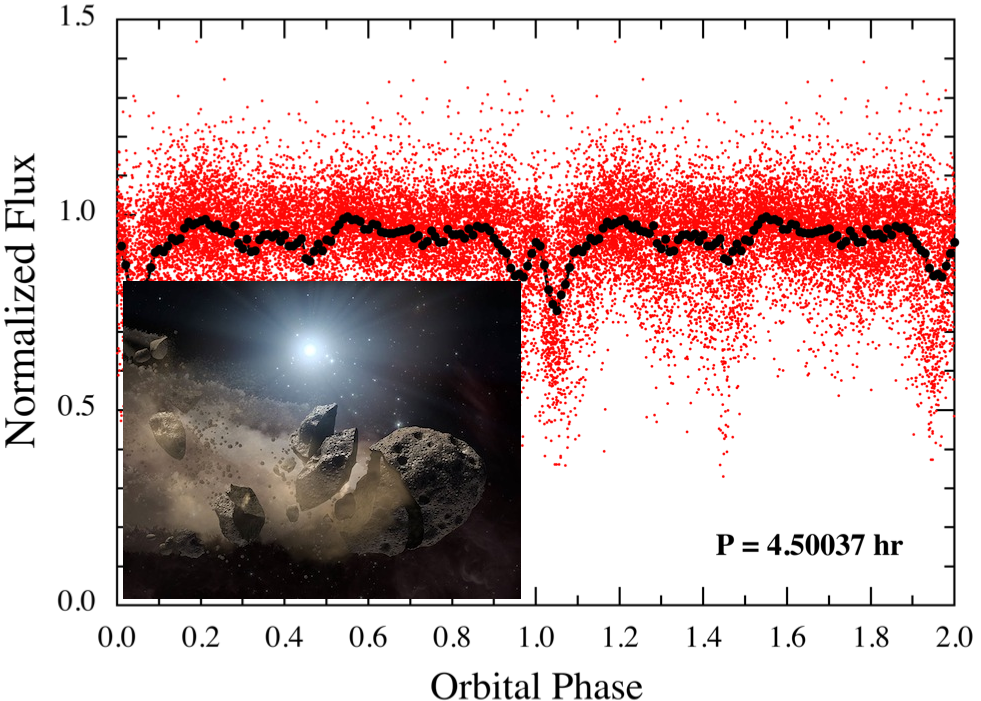

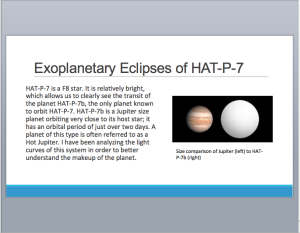

On the Edge: Exoplanets with Orbital Periods Shorter Than a Peter Jackson Movie

In this presentation, I discussed the work of our Short-Period Planets Group (SuPerPiG), focused on finding and understanding this surprising new class of exoplanets. We are sifting data from the reincarnated Kepler Mission, K2, to search for additional short-period planets and have found several new candidates. We are also modeling the tidal decay and disruption of close-in gaseous planets to determine how we could identify their remnants, and preliminary results suggest the cores have a distinctive mass-period relationship that may be apparent in the observed population. Whatever their origins, short-period planets are particularly amenable to discovery and detailed follow-up by ongoing and future surveys, including the TESS mission.