Among different fields of science, astronomy has a unique history of citizen science projects. In the last few decades, the advent of user-friendly software and web infrastructure, as well as off-the-shelf research-grade instrumentation, has led to a golden age of citizen science astronomy. Opportunities for amateurs to contribute meaningfully to astronomical research have never been more plentiful.

Halley’s Eclipse

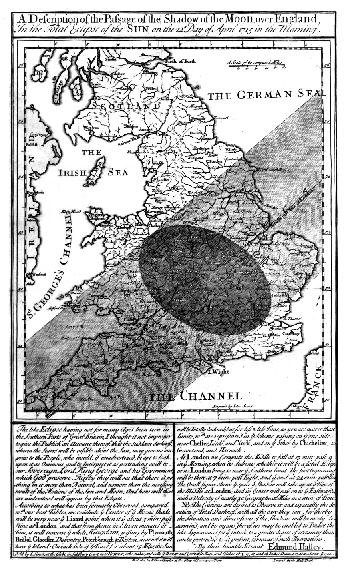

One of the first large-scale citizen science projects, English polymath Edmond Halley of Halley’s Comet fame recruited amateur astronomers across Britain to observe a solar eclipse predicted to occur in summer 1715. Halley made a map (shown at left) for where he expected the eclipse track to pass and then asked the amateurs observe and time the eclipse.

By combining these data with the locations of the observers, Halley was able to update the Moon’s orbital motions, which led eventually to the discovery that the Earth’s rotation has been slowing down due to tidal interactions with the Moon.

Not-So-Amateur Astronomy

One of the biggest recent citizen science astronomy projects is the Galaxy Zoo program. Tapping into the power of crowdsourcing, Galaxy Zoo started in 2007 and invited people to help identify the shapes of different galaxies, a task very difficult for a computer to complete unassisted.

The shape of a galaxy — whether elliptical, spiral, or barred spiral — relates to its evolution and interaction with other galaxies but in ways we don’t fully understand. Galaxy Zoo’s enormous catalog of 1.5 million notated galaxies is helping astronomers tease out the relationships between a galaxy’s morphology and its evolution. As of 2017, data from Galaxy Zoo has made their way into more than 60 scientific publications.

Under the Milky Way

As fun as classifying galaxies might be for some amateurs, others might want to get out under the night sky and collect their own data to contribute. The ready availability of research-grade hardware and software is now rendering such efforts almost trivially easy.

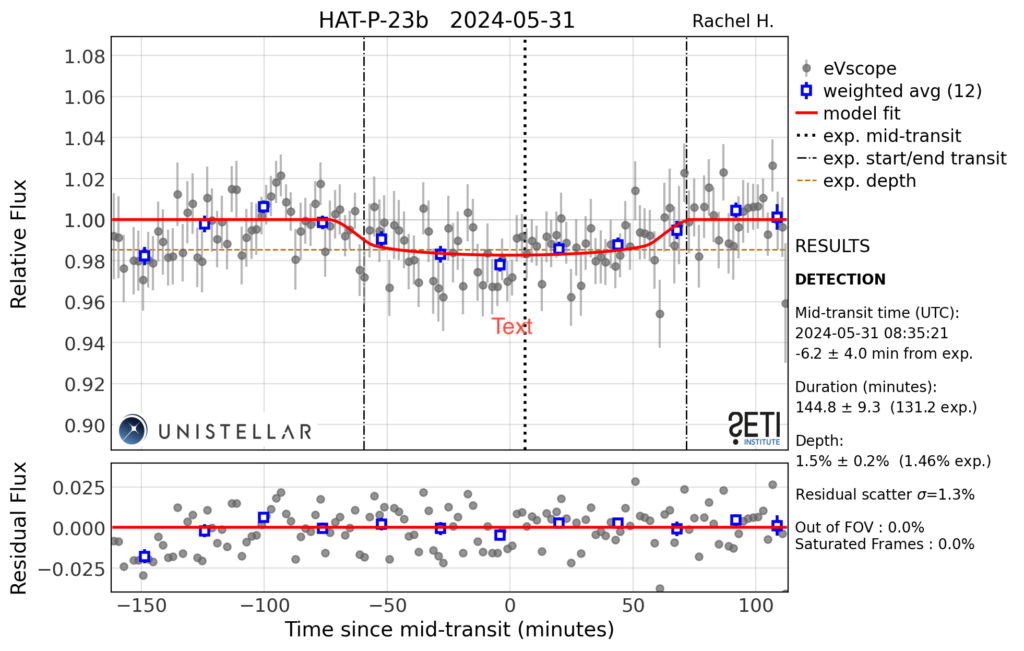

For example, the company Unistellar has several models of telescope that involve automated tracking of the sky, as well as a digital imager. The software used to control the scopes even has a citizen science observing mode. Users can select one of several different kinds of observing, including asteroid occultations, exoplanet transits, and cometary observations. Then, based on the user’s location, the software will determine what objects might be visible. Users OK the selections, and then the scope can collect the requisite data. Unistellar even has an online repository to which the collected data can be uploaded.

The same online repository also includes software to process these data and provide the user with a final data product. The image above shows an exoplanet transit that was observed by our group using our Unistellar scope from Boise State’s campus.

Want to learn more about citizen science astronomy? Join Boise State Physics on Fri, Sep 6 at 7:30p MT on Boise State’s campus to hear Dr. Franck Marchis of the SETI Institute discuss his citizen science work with Unistellar.