Borrowed from @GijsMulders — https://twitter.com/GijsMulders/status/789626580058251264.

The last day of the meeting is always to hardest to write about because I’m usually so busy wrapping things up, I don’t have time to write (hence my writing this post from Boise on the Sunday AFTER the conference).

In any case, lots of talks and goodbyes on the last day, but one talk that stands out for me came from Andrew Hesselbeck Hesselbrock, one of David Minton‘s grad students at Purdue’s EAPS. The talk tackled one of the longest-standing mysteries in solar system science: Why hasn’t Phobos crashed into Mars yet?

Mars has two tiny moons, Phobos and Deimos, which visibly resemble asteroids but are probably not for a long list of reasons.

Phobos is close enough to Mars that Mars’ gravity is dragging the moon inward, similar to but in the opposite direction as the effect of the Earth’s gravity on the Moon. Phobos is so close, in fact, that astronomers expect it will spiral into Mars in just a few million years.

Phobos and Deimos have probably been orbiting Mars for about the age of the solar system, 4.6 billion year. So if this orbital decay were the whole story, it would be mean we just caught Phobos right at the end of its life, about as likely as catching someone driving from Boise to New York City right as they pass through the Holland Tunnel*. Hesselbeck Hesselbrock suggested in this talk that we’re actually seeing a recurring phase in a much more dramatic story for Phobos.

Instead of steadily spiraling in toward Mars for 4.6 billion years, Phobos (or at least a proto-Phobos) already spiraled in toward Mars before, millions of years ago. But when the satellite got close enough to Mars, Mars’ gravity ripped it apart and formed a disk of rubble around the planet. Soon after forming, this disk spread out, some moving toward Mars (and ultimately impacting the surface) and some moving away. Eventually, the bits that moved outward moved far enough away from Mars that they re-coalesced. In fact, Hesselbeck Hesselbrock speculated that Phobos has actually been reincarnated many times in this way, every time a little smaller than before, until we were left with the bitty moon we see today.

As crazy as this hypothesis sounds, it could answer several puzzles of the Martian system, including accounting for cyclic sediment deposits on Mars’ surface — the deposits form every time Phobos falls aparts and bits rain down on Mars’ surface.

Again, the annual DPS meeting astounds and amazes. Looking forward to Provo next year.

The distance from Boise to New York City is about 2,475 miles, and the Holland Tunnel is about 9,000 feet long. Assuming a uniform driving speed, the probability of catching our driver in the tunnel is roughly equal to 9,000 feet/2,475 miles ~ 0.1%. The probability of catching Phobos during a 10 million year window over the age of the solar system is about 0.2%. Of course, you’re a little more likely to catch our driver in the Holland Tunnel, given NYC’s traffic.

First up was

First up was  This presentation was followed by

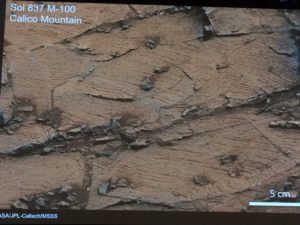

This presentation was followed by  Gupta described how the tilt of beds of sedimentary rock could be used to infer the presence of a river delta spilling out into the crater, which suggests the existence of a long-lived (millions of years) lake in the crater, probably billions of years ago

Gupta described how the tilt of beds of sedimentary rock could be used to infer the presence of a river delta spilling out into the crater, which suggests the existence of a long-lived (millions of years) lake in the crater, probably billions of years ago