Journal Club

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2022JE007605

Daedalus’ situation was desperate: to keep the secret of the labyrinth, King Minos had trapped its creator, Daedalus, and his son Icarus in the maze with the man-eating Minotaur. In a fit of inspiration, Daedalus crafted two pairs of wings of feathers and wax. As they flew out over the Aegean Sea, Daedalus admonished Icarus not to fly too close to the Sun or else the wax holding the feathers would melt.

Famously full of flawed physics, this fabulous fable foreshadows the forbidding future for a planet newly discovered using data from NASA’s TESS Mission. Dubbed a “warm Jupiter”, TOI-3362 b swings around its host star every 18 days. Like Jupiter, it is a gas giant planet (with a mass five times greater than Jupiter’s), but, unlike Jupiter, It sweeps past its host star every 18 days on a wildly elongated orbit that flash-heats the planet. And like Icarus, TOI-3362 b will one day plunge disastrously into the sea (although in this case, it’s not the warm Aegean but a sea of molten plasma).

Continue Reading

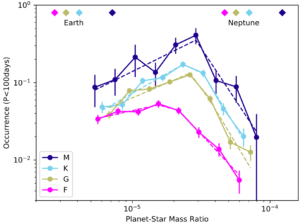

Figure 1: The number of planets per star as a function of the planet-star mass ratio as discovered by Kepler. Dark and light blue curves are for stars less massive than the Sun, while the pink curve is for more massive stars. From Pascucci et al. (2018).

Among the mind-blowing discoveries of the Kepler Mission is that the most common type of planet in the galaxy is the super-Earth/sub-Neptune. This unexpected type of planet straddles the boundary between Earth and Neptune in size and mass, and so they may be super-sized rocky planets or anemic gas-rich planets. We just can’t tell.

Stranger still is that this bizarre chimera orbits one out of every four stars in the Milky Way, but we don’t seem to have one in our solar system (unless the Planet Nine hypothesis pans out).

If that wasn’t enough to make you feel like a planetary outsider, a recent study suggests most planet systems have very different architectures from our own.

In their paper, Prof. Ilaria Pascucci of the University of Arizona and her colleagues studied the distribution of masses for planets discovered by the Kepler Mission. Unlike other recent work, though, they considered not just the planet masses but how they compare to the masses of their parent stars.

Naively, we might expect that more massive stars grow more massive planets, and there is good evidence that more massive stars host more massive dust disks. So as long as the processes that make planets are happy to operate around most any kind of star, then we can use the distribution of planet-star mass ratios to disentangle the influence of stellar mass from other effects.

And Pascucci et al. found exactly what we expected – big stars, small stars, they are all more likely to host planets more massive than Earth — but only up to a point. As shown in Figure 1, the number of planets per star increases with the planet-star mass ratio until it reaches about 0.00003 (or 10 Earth masses for one solar mass) — somewhere between the Earth and Neptune. Above that ratio, the occurrence rate drops, meaning more massive planets are less and less common.

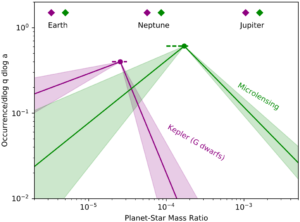

But something even more interesting emerged when Pascucci et al. compared their results based on the Kepler Mission to other surveys. Because Kepler is good at finding planets close to their host stars and not at finding planets farther away, Pascucci’s results don’t tell us much about planets in orbits like Jupiter’s. But microlensing surveys, which use a totally different planet-finding technique, *are* good at finding these more distant planets.

Figure 2: The number of planets around each star with a given planet-star mass ratio for planets close to their host star (as found by Kepler) and planets farther away (as found by microlensing surveys). From Pascucci et al. (2018).

Comparing mass ratios from the two kinds of surveys, Pascucci et al. showed more distant planets found by microlensing also show a preference, but for a ratio several times larger than what’s preferred by closer-in planets — somewhere between Neptune and Jupiter in mass, as shown by the figure above.

What does this all mean? Apparently, the universe seems to like make planets about ten thousand times less massive than their host stars, whether the stars are tiny red dwarfs or massive F-stars. And the farther away the planet is from its star, the more likely it is to be more massive.

Standard planet formation theory predicts this trend: protoplanetary disks (from which planets form) have more solid, icy material farther from the host star, and more solids means more planet.

But these results also make our solar system look even stranger than before. In most solar systems, orbits like Earth’s (and closer) are occupied by planets somewhere between Earth and Neptune in mass, and more distant orbits like Jupiter’s are occupied by planets between Neptune and Jupiter.

It’s tempting to speculate that things that make the solar system unique in one way (in this case, the type of planets we have) are related to other unique things (like, the fact that there’s life here). We don’t know much about super-Earths, but if they turn out to be more Neptune- than Earth-like, it’s not hard to imagine they wouldn’t be good places for life to get started.

Life as we know it needs a planet with a solid surface and lots of liquid water, and so maybe it’s not surprising we haven’t found life elsewhere in the galaxy yet: most of the planets are lifeless, gas balls.

With the very first discovery of an exoplanet around a Sun-like star (51 Peg b), astronomers were introduced to hot Jupiters. These totally unexpected planets resemble Jupiter in mass, composition, and size, but they have orbits that nearly skim the surfaces of their host stars. Some of them are even losing their atmospheres under the apocalyptic glare of their host stars.

How their lives began remains a mystery, but we have a pretty good idea of how their lives will end – they will be engulfed or torn apart by their host stars. That’s because hot Jupiters are big and close enough that they can actually raise a tidal bulge on the stars (and we can actually see the bulge in a handful of cases).

This tidal interaction can cause the planets to spiral downward toward the stars, and at the same time, it causes the spins to spin faster until the planet is destroyed by the star. The same tidal effect, just in reverse, is driving the Moon away from the Earth, while slowing down the Earth’s spin. But here’s the key: we don’t know how quickly the planets are spiraling in.

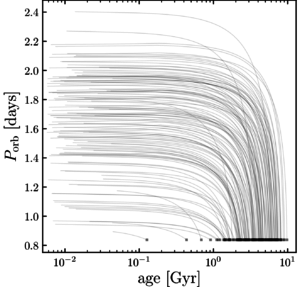

Tidal decay of planetary orbital period over billions of years (Gyrs). From Penev et al. (2018 – https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.05269).

Enter Prof. Kaloyan Penev of UT Dallas Physics Dept. On Valentine’s Day last week, he and his colleagues published an academic love note exploring planetary tidal decay. To do this, they modeled the evolution of planetary orbits and stellar spins under the influence of tides. The tracks in the figure at left show how a planet’s orbital period (or distance from its star) might shrink over billions of years, thanks to tides. The clump of spaghetti noodles in the figure shows that evolution for a range of assumptions about the rate of decay.

By comparing the stellar spin rate and planetary orbit predicted by their model to those we actually observe for each system, Penev and colleagues showed that the tidal decay rates might actually slow down as the planets approach their stars. So perhaps instead of an reckless death dive into the star over a few million years, the planets make like Zeno’s tortoise and tiptoe closer and closer without plunging in.

Upcoming surveys such as the TESS mission and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope may soon allow us to test whether planets do or do not plunge into their stars. Theoretically, we expect stars that eat their planetary children dramatically brighten up by a factor of 10,000 over a few days – faster than a supernova brightens but nowhere near as bright. These surveys might able to see stars engaged in this act of cosmic infanticide.

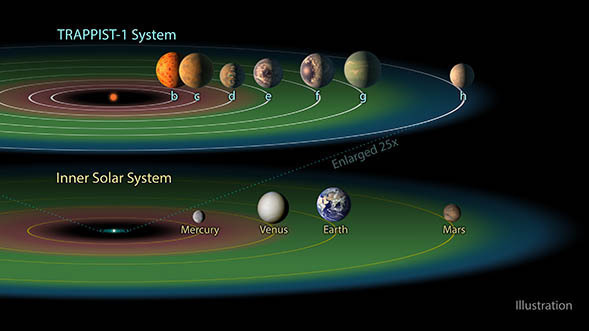

Comparing the TRAPPIST-1 system to the solar system. From http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/images/6294-ssc2017-01h-The-TRAPPIST-1-Habitable-Zone.

In astronomy, when you look for evidence supporting a hypothesis and don’t find it, that’s called a “null result“. The null result is usually not all that exciting, but last week, an attempt to detect the atmospheres of potentially habitable exoplanets came up null, and that, as it turns out, may mean the planets are habitable.

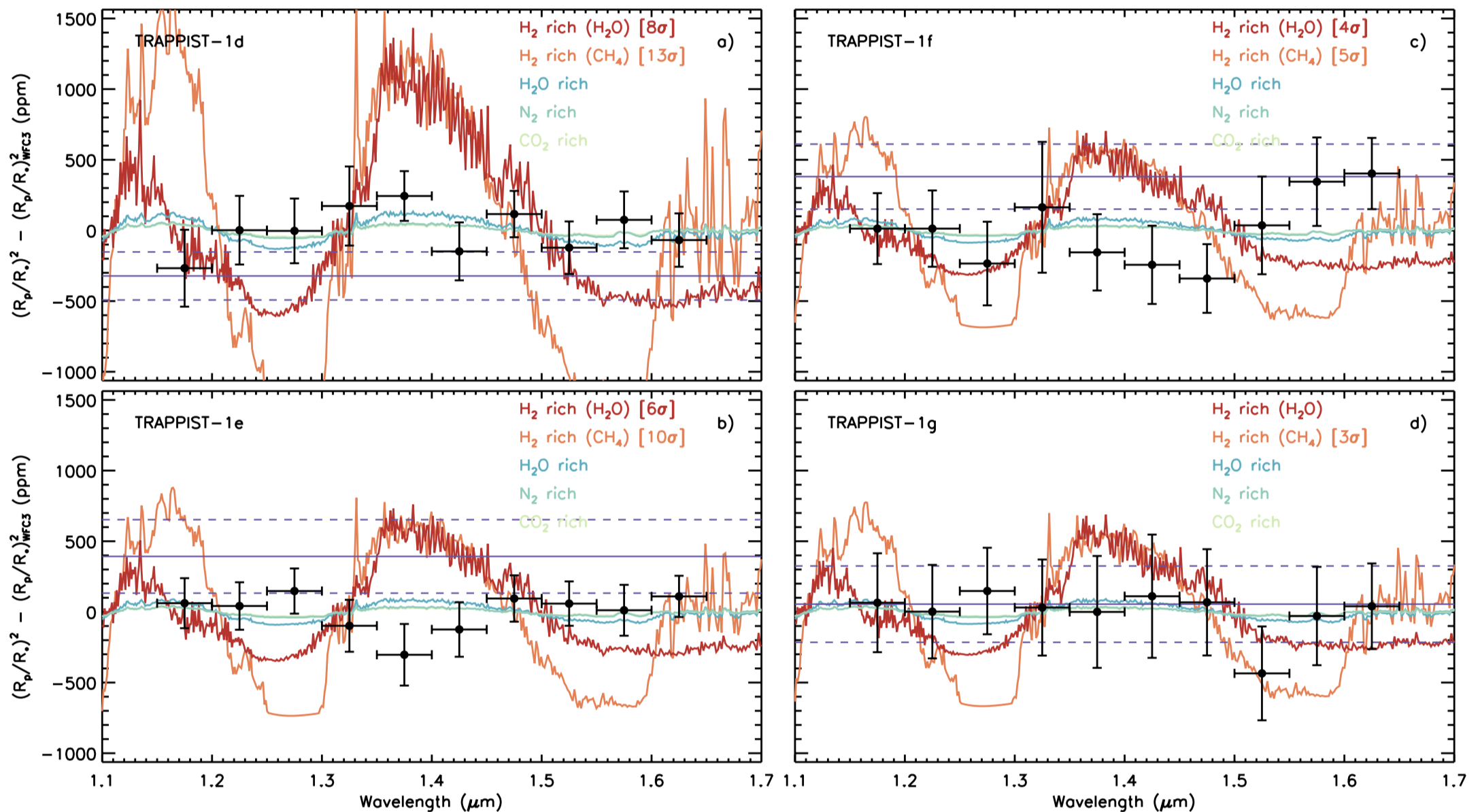

In a recent study published last week in Nature Astronomy, Dr. Julien de Wit of MIT and colleagues observed the transits of four of the planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system. The discovery of this system was announced last year and generated a lot of interest — it comprises seven Earth-sized planets orbiting a red-dwarf star, and at least four of the planets orbit in the star’s habitable zone. So astronomers are scrambling to determine the climatic conditions on these planets and find out whether they host life.

Key to those conditions is the composition of the planets’ atmospheres, and the best way to probe atmospheres lightyears distant is to detect the colors of the planets’ shadows as they pass in front of their host stars, i.e. as they transit. When light from the star passes through a planet’s atmosphere, the cool gases can imprint spectral signatures, which we can then detect using a very sensitive telescope — de Wit used the Hubble Space Telescope.

Now, even though the TRAPPIST planets are Earth-sized, that doesn’t mean their atmospheres are Earth-like — astronomers have founds lots of weird planets in the last several years. The atmospheres could be hydrogen-rich like Jupiter, hydrocarbon-rich like Neptune, or rich in nitrogen and oxygen like Earth.

In principal, each kind of atmosphere would give a distinct spectrum, but in practice, atmospheres rich in hydrocarbons or nitrogen, potentially good atmospheres for life, are difficult to detect because they are weighty and drape over the planet like a heavy blanket. By contrast, a hydrogen-rich atmosphere, although probably not great for life, can be light and fluffy, relatively easy to detect.

When de Wit and colleagues analyzed transit data they collected from Hubble showing transits for planets TRAPPIST-1 d, e and f, they found no atmospheric signals down to their detection limits. The spectra below show this lack of atmospheric coloration and what they would have detected if the atmosphere was hydrogen-rich.

Now, of course, this non-detection does NOT mean the planets are habitable or even Earth-like. As the figure shows, their atmospheres could still be radically different from the Earth’s (drenched in water vapor or carbon dioxide-rich like Venus), but it rules out the possibility that they are Jupiter-like — potentially good news for life there.

Very likely, when the James Webb Space Telescope finally launches next year, the TRAPPIST-1 system will be one of its first targets. JWST’s vastly improved sensitivity will help reveal not just a potent null result for the TRAPPIST-1 system but may also reveal the glimmer of distant Earth-like worlds.

Spectra for TRAPPIST-1 d, e, f, and g. From de Wit et al. (2018) – https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-017-0374-z.

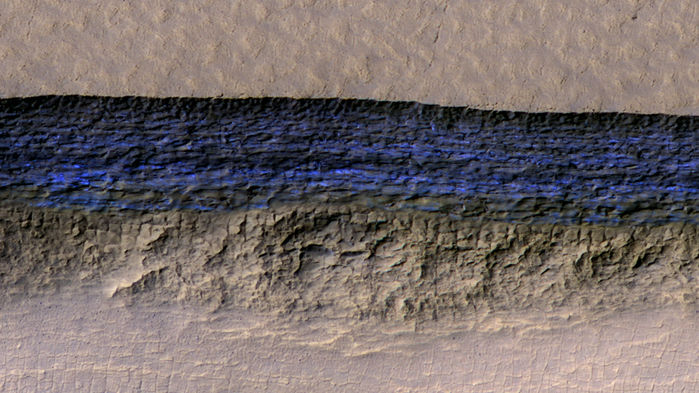

Enhanced color image of the thick bands of ice (blue) have been spotted in steep cliff faces. NASA/JPL/UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA/USGS

At last week’s journal club, we discussed a recent paper that reports the discovery of ancient glaciers on Mars.

Dr. Colin Dundas of the USGS’s Astrogeology Group based in Flagstaff spotted these buried ice cliffs during his daily scan of the regularly collected images taken by the HiRISE camera onboard Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) currently circling Mars. (The camera itself is pretty stunning – it produces orbital images of Mars at high enough resolution that you could almost read the headline on a martian newspaper, assuming they had newspapers.)

In scanning through the daily haul of images, Dundas spotted striking blue strata in the walls of steep cliffs just a few meters below the dusty martian surface that sure look like water ice. Follow-up spectral observations by CRISM instrument on MRO confirmed the cliffs were indeed almost completely pure water ice, with no more than with less than 1% dust.

Ice on Mars isn’t particularly surprising – astronomers have known (or at least suspected) there is water ice at the poles of Mars for more than 100 years, and a mountain of data has indicated vast stores of ice in Mars’ subsurface, especially near the poles. But key questions about this ice have persisted: Was the ice recently deposited, and how much dust is mixed in?

Since these newly discovered cliffs are so pure, though, Dundas and colleagues suggest that they were probably deposited as snow before being buried. Mars’ current climate isn’t really conducive to water snow, and so the ice was probably deposited millions of years ago, when Mars’ axis had a very different tilt resulting a very different climate from now. The fact that the ice cliffs occur much nearer to the equator than might be expected also points to formation during a previous climatic epoch.

The implications of these cliffs for Mars’ climate history aren’t entirely clear, but their importance for exploration of Mars is hard to overstate. As Dundas et al. say in their paper, the cliffs would very likely serve as a resource for future human visitors. The water could be combined with gases in the martian atmosphere to make rocket propellent and even oxygen.

So there are large deposits of ice in the subsurface of Mars? Maybe “Total Recall” wasn’t so much science fiction as science prophesy.

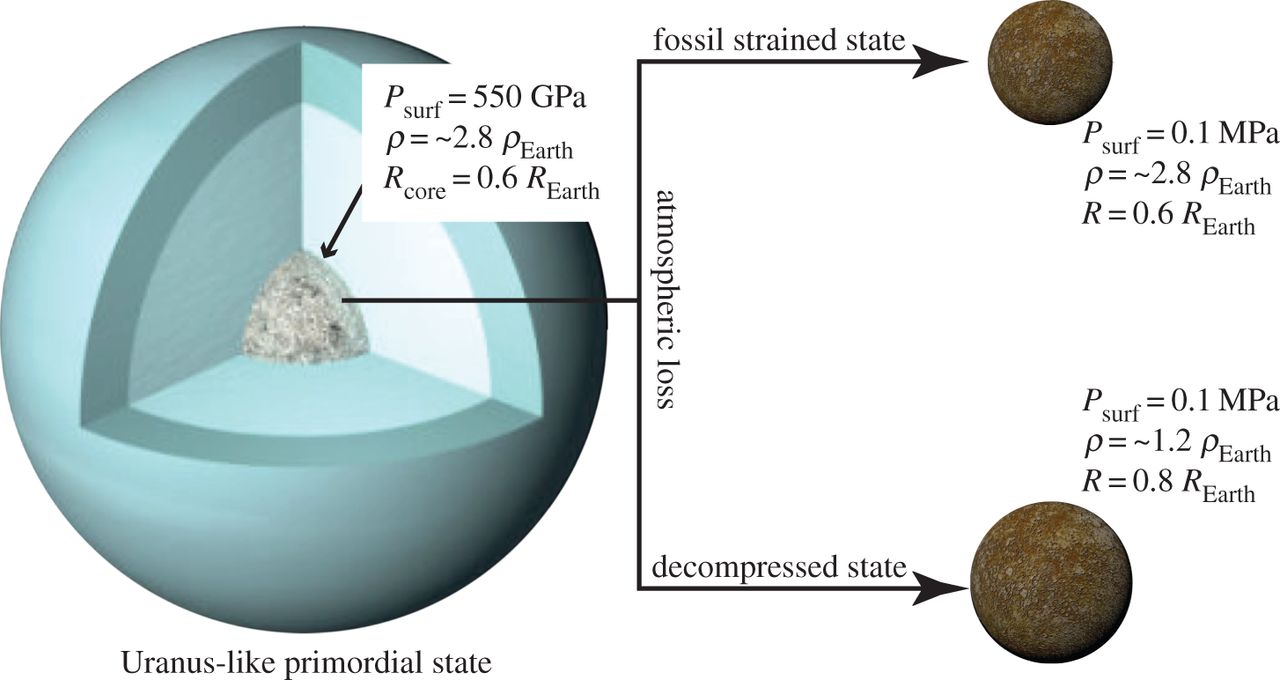

Figure from Mocquet et al. (2014) show how a gaseous planet might evolve into a dense, rocky core.

Another blast from the past, Mocquet et al. (2014) was the topic of our journal club this week, a paper that seeks to answer the question “What would Jupiter look like if you took away its atmosphere?”.

Given the enormous number of gas-rich exoplanets very close to their host stars discovered in recent years, many astronomers (including myself) have wondered whether such planets could have their atmospheres completely removed.

We certainly see some very hot planets where intense sunlight is blasting away their atmospheres, and in other cases, the star’s gravity can rip off the atmosphere. And so it’s not crazy to think some gaseous planets might completely lose their atmospheres.

Would anything be left over? Astronomers think that gas giants like Jupiter are like big cherries, with a squishy outer layer of gas wrapped around a dense pit of rock. Indeed, the Juno mission currently in orbit around Jupiter is designed to measure the size of Jupiter’s core by measuring its gravitational field very precisely.

And so the cores of gas giants are under enormous pressure – for instance, the core of Jupiter is being squeezed by 45,000 times the pressure at the bottom of the Mariana Trench on Earth.

In their study, Mocquet and colleagues explore what happens to a rocky core under such large pressures. Not surprisingly, they find that such a core would have an enormous density, perhaps three times larger than the Earth’s.

But what is surprisingly is that their results suggest the core might retain a very large density even if you removed the overlying atmosphere. It’s as if you squeezed down a nerf ball and then let it go – instead of springing back immediately, the nerf ball would take a few billion years to decompress. This means that we might be able to identify the cores of former gas giants by looking for planets roughly the size of Earth but with anomalously high densities.

And in fact, such planets have been found – the planet Kepler-57 b has a mass more than 100 times Earth’s but squeezed into a volume only ten times larger, giving a density of almost 44 grams per cubic centimeter – twice the density of the densest element on Earth, osmium.

So in their search for fossils, gas giant paleontologists should keep in mind that the bones of extinct gas giants may have distinctively large densities, almost as dense as adamantium.

Artist’s conception of a protoplanetary disk from which planets form.

During today’s research group meeting, we discussed a paper from a few years ago from Lars Buchhave and colleagues that investigated the relationship between the composition of a planet-hosting star and the properties of its planets.

The discoveries of thousands of exoplanetary systems in the last few decades has revealed the bewildering variety of planets formed in our galaxy, and the richness of this planetary zoo probably reflects the wide range of conditions in which these planets formed.

Going back to the philosopher Kant, planets have been thought to form in disks of gas and dust leftover after their host star forms, and we now have a plethora of observational and theoretical evidence supporting this idea.

This idea means that the star and planets form mostly from the same source of material. However, while stars form directly out of the disk, the formation process for planets is a little pickier about what goes into the planets.

For example, the Sun is made almost entirely out of hydrogen and helium, elements that constitute most of the baryonic matter in the universe, while the Earth is made mostly of rocky elements, which are pretty rare in the universe. The gas giant Jupiter is kind of a mix – it’s mostly hydrogen and helium like the Sun, but it has more of the heavier elements than the Sun, all of which astronomers refer to as metals.

In their paper, Bucchave and colleagues report estimates of the ‘metallicities‘ or the amount of metals in lots of planet-hosting stars and try to figure if the type of planets around a star depends somehow on stellar metallicity.

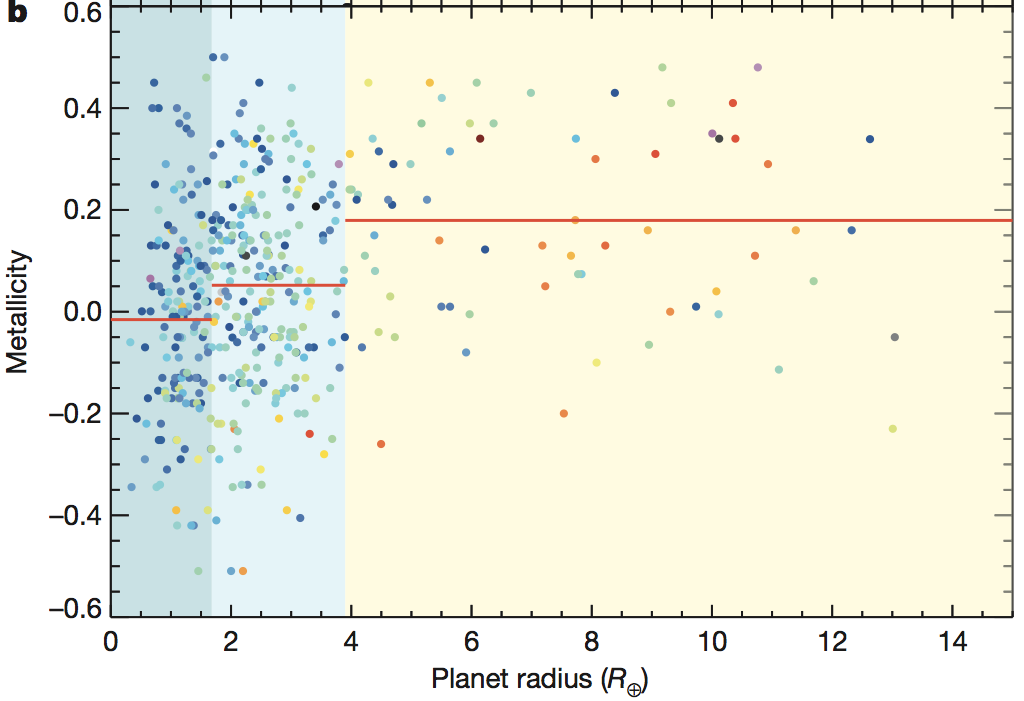

Figure 1 from Bucchave et al. (2014) shows the metallicities of stars vs. the radii (in Earth radii) of their planets. The horizontal red lines show the average metallicity for stars in that group.

Interestingly, the metallicities suggests there are three kinds of planetary systems – shown as dark blue, light blue, and yellow in the figure above. Big gaseous planets like Jupiter, with radii many times Earth’s, seem to form preferentially around stars with lots of metals, while small planets like the Earth aren’t as picky – they’ll form around stars with any metallicity. And planets with radii in between, about 2 to 4 times the Earth’s radius, they’re like Goldilocks and prefer stars with a little more metals but not too much.

What does all this mean? Astronomers think the protoplanetary disk (and therefore the star) might be required to have lots of planet-forming materials (that is, metals) in order to make big planets like Jupiter. On the other hand, forming small planets like the Earth apparently doesn’t take much because even stars with a tenth the Sun’s metals host them. Which all sort of makes sense.

But these results don’t answer everything. Why, for example, aren’t the stars with really big metallicities (the blue dots near the top left of the figure) always able to form big, Jupiter-like planets? This cluster of three blue dots are all members of the KOI-3083 planet system, whose star is Sun-sized but has almost three times more metals, but all the planets are smaller than Earth.

Could there be big planets in that system we haven’t found yet? Or maybe the planet formation process involves so much randomness (stochasticity) that a big metallicity only steers the system in the direction of big planets; it doesn’t force them in that direction. Like gently shepherding a toddler through a toy store – more often than not, you’ll end up with toys in your cart.

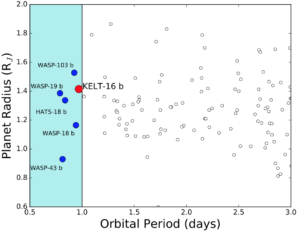

The radii Rp and periods P of KELT-16 b, along with lots of other short-period planets. From Oberst et al. (2017).

There’s a new paper from the KELT Survey and led by Prof. Thomas Oberst from Westminster College announcing the discovery of another exoplanet in a very small orbit, nearly skimming the surface of its host star: KELT-16 b is a highly irradiated, ultra-short period hot Jupiter nearing tidal disruption.

These planets have been something of a puzzle since the first was discovered back in 1995. Like Jupiter, they are mostly made out of hydrogen and helium gas, but unlike Jupiter, they orbit very close to their host star, which probably means they didn’t form where we see them today.

Even among hot Jupiters, though, KELT-16 b is an outlier. It’s one of a handful of hot Jupiters with orbital periods less than 1 day (as compared to Jupiter’s orbital period of 12 years), so whatever processes led to its origin are cranked up to 11 for KELT-16 b and its ultra-short period siblings.

The mystery of its origins aside, its short period means KELT-16 b is probably a good candidate for follow-up observations of its atmosphere, particularly by the James Webb Space Telescope. But tidal interactions with its host star means it may get eaten by its host star in less than a million years, so we need to get those observing proposals submitted soon.