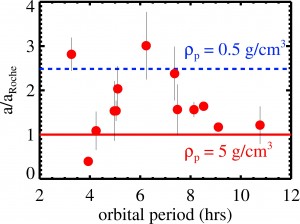

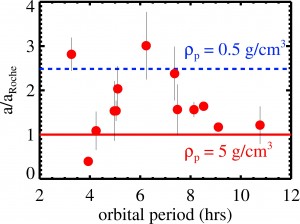

Figure 20 from Jackson et al. (2013) showing the distance from their host stars at which planets would be torn apart (solid red line).

Today I submitted a new paper for publication, “A Survey for Very Short-Period Planets in the Kepler Data.” Our new survey of data from the Kepler planet-hunting mission has revealed planetary candidates with orbital periods as short as three hours, so close to their host stars they are nearly skimming the stellar surface.

We used data from the Kepler mission, which finds planets using the transit method — by looking for their shadows as the planets pass between their host stars and the Earth. Since the planets are so far from the Earth, we can’t see them directly and instead only see the little dip in brightness of the host star as the planet passes in front of it.

Over the last few decades, astronomers have found a breath-taking menagerie of exotic planetary systems, and the candidate planets we found in this paper are no exception: more than 100 times closer to their host stars than the Earth is to the Sun, if these candidates turn out to be rocky planets, their surface are baking at nearly 5,000 degrees F (3000 K), producing giant lakes of molten rock.

In fact, these planets are so close to their host stars that they are on the verge of being torn apart by the stars’ gravity. The figure at left shows the orbital distances for these planets (red dots) relative to the distance at which they would be torn apart (shown by the red line). The blue line shows where they would have been torn apart if, instead of being rocky, they were more like hot gas giant planets.

We’ve still got some work to do to make sure these candidates are actually planets, but if confirmed, they would be some of the closest planets to their stars ever discovered, once again overturning what astronomers thought we knew about where planets can live and what they’re like.