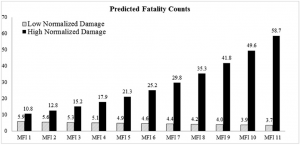

Predicted fatality counts. MFI indicates masculinity-femininity index (1 -> very masculine name, 11 -> very feminine name), and hurricanes with low MFI (vs. high MFI) are masculine-named (vs. feminine- named). Predicted counts of deaths were estimated separately for each value of MFI of hurricanes, holding minimum pressure at its mean (964.90 mb).

We discussed a very interesting paper today in Journal Club, Jung et al.’s (2014) study of correlations between the perceived masculinity-femininity of a hurricane’s name and its death toll. As reflected in the figure at left from the paper, the higher the masculine-feminine index for a hurricane (MFI, 1 -> very masculine name, 11 -> very feminine name), the larger the predicted fatality count. As a specific example, Jung et al. estimated that Hurricane Eloise (with a decidedly female MFI = 8.944) killed three times as many people as Hurricane Charley (MFI = 2.889).

Jung et al. also polled participants and found they consistently rated female storms as less likely to be severe and indicated they were less likely to evacuate in the wake of female storms, perhaps due to implicit gender biases. Ostensibly, their results suggest a lot of lives could be saved by simply not using female names for hurricanes.

But there are a lot of questions that were not addressed by the study, and others who have looked at the data have pointed out important unresolved issues.

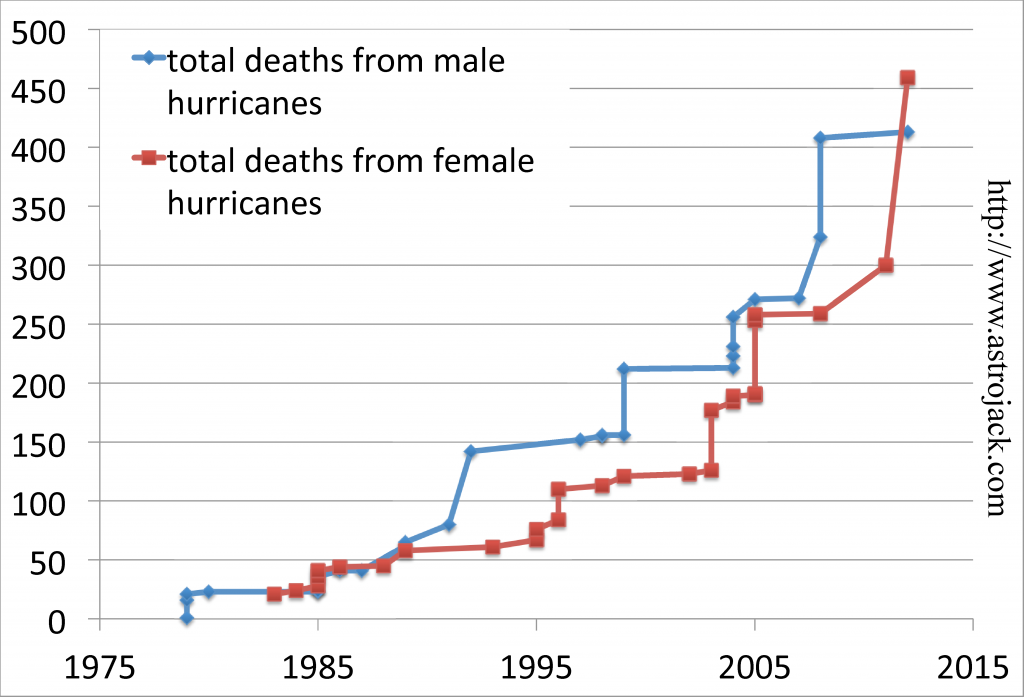

A blog entry at Prooffreader.com pointed out that the authors should only have considered hurricanes after 1979 since there were no male hurricane before then. The blogger showed that, comparing total hurricane deaths since both male and female names have been used (1979), male hurricanes killed more people (413 total) until just two years ago, when Hurricane Sandy brought the total for females to 459. And this result used the authors’ own data. The plot at right is a recreation of the Prooffreader.com plot.

The plot at right is a recreation of the Prooffreader.com plot.

I spent several hours yesterday, poring over the paper and have to admit that I did not understand the statistical methods employed. The authors don’t give a lot of details, and the key references for the techniques seem to be two textbooks to which I don’t have access.

The paper talks about using a model to estimate the number of deaths for a storm of a given severity, but to the extent that I can compare their predicted death tolls to actual, the model seems pretty discrepant with the data. For example, their model estimates that Hurricane Eloise killed 41.45, but the actual number killed was 21. They also estimated Hurricane Charley killed 14.87, whereas Hurricane Charley from 1986 killed 5 and the one from 2004 killed 10 (they don’t say which Charley they meant).

So Jung et al. present a very interesting idea, but it’s not at all clear that their results hold up. I’m sure this paper will prompt a spat of sociological studies into hurricane statistics, though, which will probably lead to additional disaster preparedness and save lives.