An usually active Sun has given us some especially brilliant and visible Northern Lights in recent months. For Boise State Physics’ July 2024 First Friday Astronomy event, we’ll host Dr. Elizabeth Macdonald, director of NASA’s Aurorasaurus project. In preparation for that event, I’ve written this short primer on the science of the Northern Lights.

What exactly are the “Northern Lights”?

As They Might Be Giants taught us, the Sun is a miasma of incandescent plasma. That means that Sun is made out of gases so hot that it glows and that its constituent particles (electrons and protons) are not as tightly linked as in every-day matter. If you’ve ever sat around a campfire, you’ve seen a plasma.

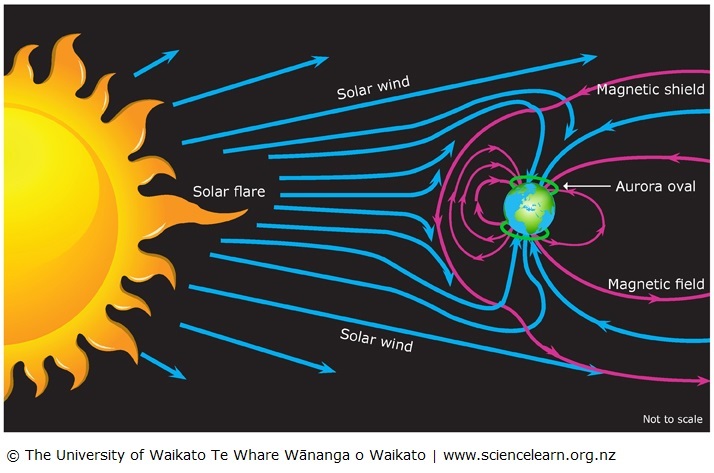

This hot plasma gets ejected from the Sun into interplanetary space and becomes the solar wind. As that solar wind gets close to the Earth, it get swept up by the Earth’s own magnetic field, which redirects the solar wind toward the magnetic poles, north and south.

The solar wind then crashes at super-sonic speeds into the Earth’s atmosphere. This high energy wind excites the atoms and molecules in the atmosphere and causes them to glow, and THAT’S what we call the “northern lights”.

Why can’t we usually see the Northern Lights? Why are they suddenly visible?

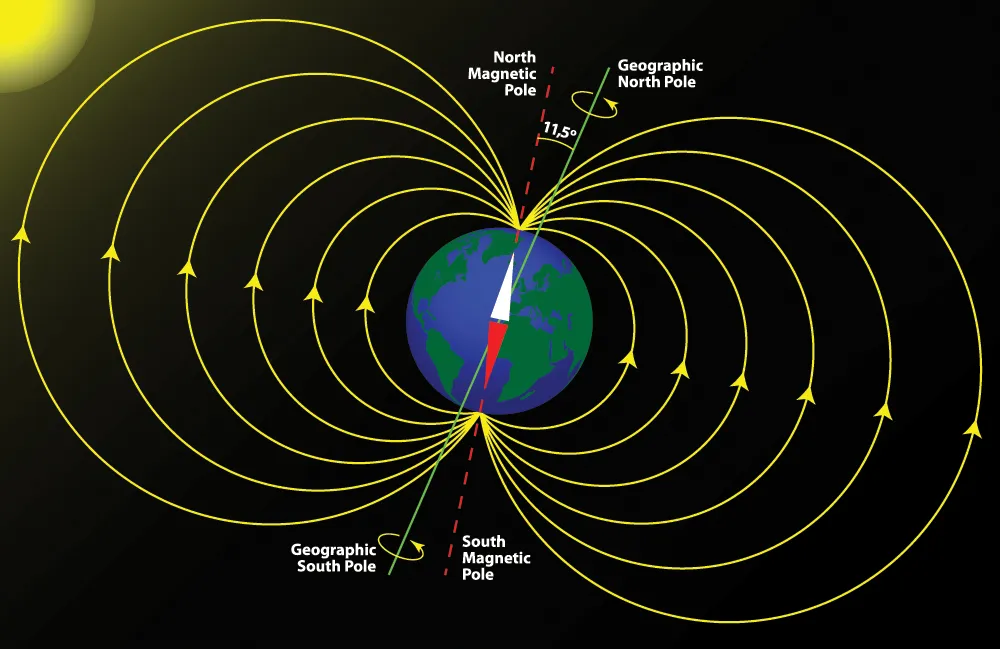

As I said above, the Earth’s magnetic field grabs the solar wind, which comes in from the Sun along the ecliptic, and redirects it toward the magnetic poles. Since the lines of force from the magnetic field pass through the Earth’s surface at the poles (see the figure above), that means, usually, the solar wind can’t hit the Earth’s atmosphere too far away from either the north or south pole.

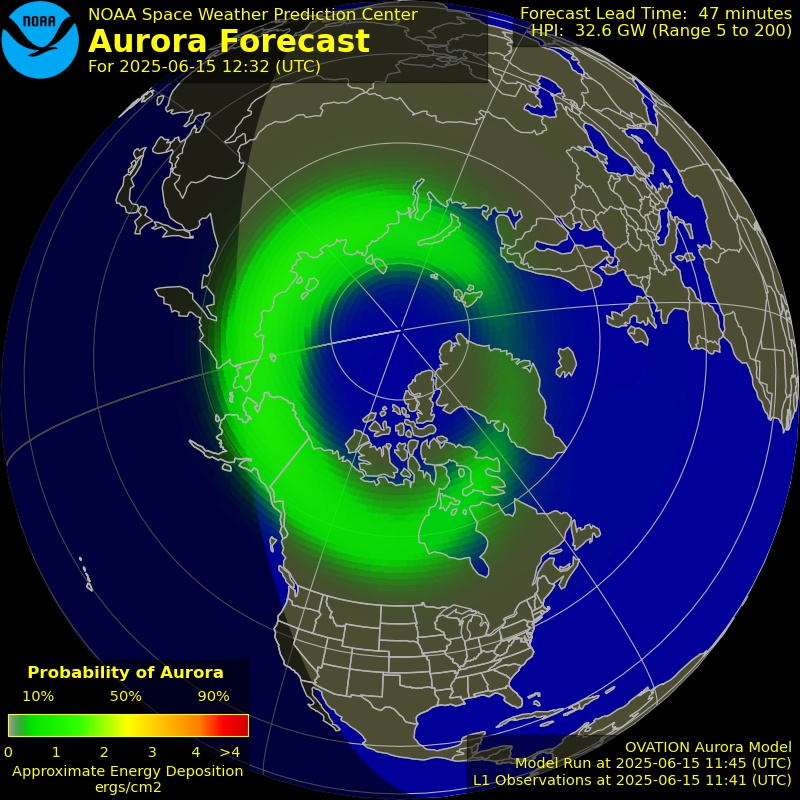

But if the solar wind is blowing very hard, then some of it can leak into the atmosphere away from the poles. And that’s what’s been happening recently: the Sun has had some usually strong magnetic storms (why, we don’t really know), and those storms have created winds stronger than normal. So we can see the lights farther away from the poles than usual.

Are the Northern Lights dangerous?

Not usually. The vast majority of the time, the Earth’s magnetic field and atmosphere protect us from the solar wind. But once in a while, the solar winds can be so strong they can disrupt satellites. Mostly, on the ground, though, we remain unaffected (unless your Dish-TV satellite goes out).

But, in 1859 during the American Civil War, there was an exceptionally large solar storm that did pose a hazard on the ground. Just after the Battle of Fredericksburg, civil war soldiers were treated to a glorious display of the Northern Lights.

This strong solar storm carried with it very strong electric and magnetic fields that disrupted the telegraph system newly installed across the US. Some telegraph offices caught fire, and apparently the solar wind-induced currents were so strong, telegraph operators were able to send messages even after they disconnected their batteries.

When’s the next time I can see the Northern Lights?

Unfortunately, like Earth weather, solar weather is very hard to predict, so we can’t say with a lot of certainly when and where the Lights will be visible. But NASA and NOAA monitor the Sun regularly and do provide short-term predictions for the Northern Lights.

If you want to learn more about aurorae and even about how you can get involved in citizen science efforts to study them, attend Boise State Physics’ First Friday Astronomy on Friday, July 5 on Boise State’s campus at 7:30p MT or online at https://boi.st/astrobroncoslive. Dr. Elizabeth Macdonald will talk about the citizen science Aurorasaurus project.