NASA’s TESS Mission launched last March and began returning data in the fall. As the worthy successor to the wildly successful Kepler Mission, TESS promises great things.

And already some of that promise is being fulfilled. Astronomers have used TESS data to find exocomets, probe the atmospheres of planets we already knew about, and most recently to find possible evidence for imminent planetary destruction.

The possibly doomed planet is WASP-4b, a gas giant planet that passes in front of its host star every 1.5 days. It orbits so close to its host star that tidal interactions between the star and planet can cause the shape of orbit to vary over time, giving rise to transit-timing variations, illustrated in the video below.

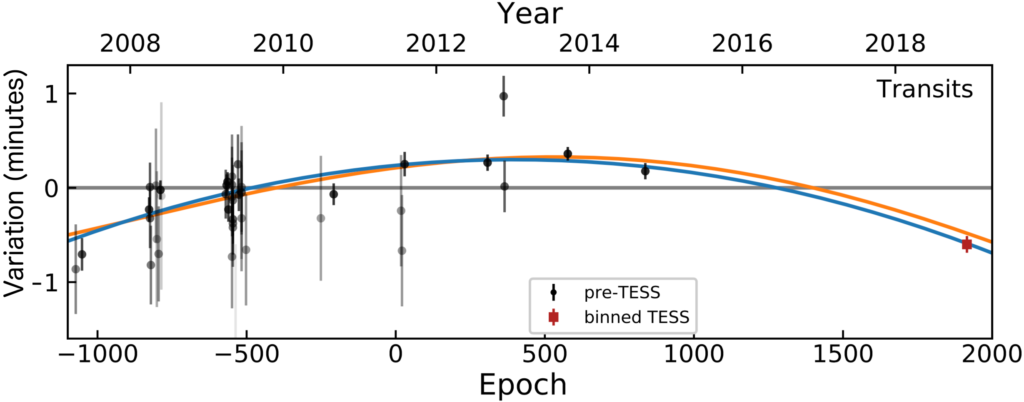

Just this week, Luke Bouma, a graduate student in Princeton astronomy, and colleagues analyzed recent TESS observations of WASP-4b to see if the data show any signs of orbital variations. Not only did they find signs of orbital variation, they found that the orbital period seems to be getting shorter, at a rate of about 12 milliseconds per year, or about one jiffy every year. This about 1000 times faster than slowing of the Earth’s day due to tidal interactions with the Moon.

It’s not clear exactly what is causing WASP-4b’s orbit to change, and Bouma explores a couple of options. One idea is that WASP-4b’s orbit is very slightly eccentric and that tidal interactions between the planet and star may be causing apsidal precession, similar to effects experienced by the Moon that complicate the timing of eclipses.

Another, and to my mind more exciting, possibility is that tidal interactions with the host star are drawing the planet inexorably inward. In that case, WASP-4b may eventually be torn apart by its host star’s gravity, a fate that may have befallen many a hot Jupiter.

The great thing about both hypotheses is that they can be tested by additional observations. In fact, amateur astronomers may be able to contribute. Indeed, there is a cottage industry of amateur astronomers observing exoplanet transits, and the hardware, software, and expertise required are pretty minimal for serious amateurs.

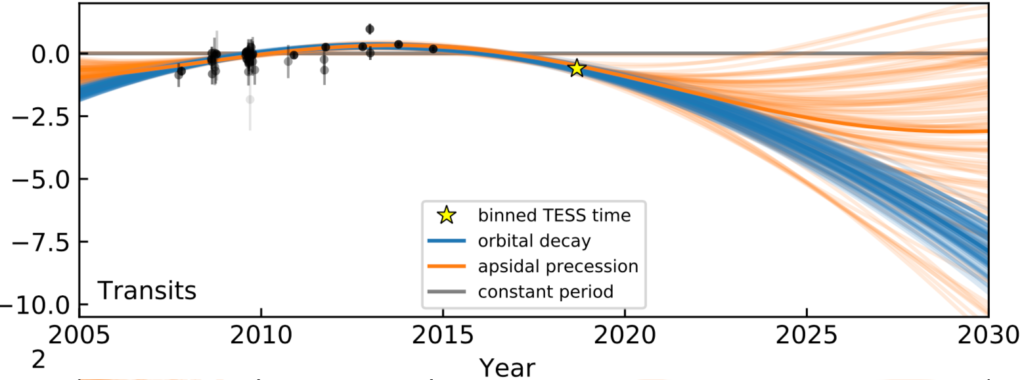

Bouma predicts that, over the next several years, WASP-4b’s orbital period might change by several minutes. If the period drops and then increases again (orange curves above), then the variations are likely due to precession, and the planet is probably safe against tidal decay.

However, if the period continues to drop (blue curves above), then the planet is likely doomed to tidal disruption in the next nine million years, short on cosmic timescales.