With the very first discovery of an exoplanet around a Sun-like star (51 Peg b), astronomers were introduced to hot Jupiters. These totally unexpected planets resemble Jupiter in mass, composition, and size, but they have orbits that nearly skim the surfaces of their host stars. Some of them are even losing their atmospheres under the apocalyptic glare of their host stars.

How their lives began remains a mystery, but we have a pretty good idea of how their lives will end – they will be engulfed or torn apart by their host stars. That’s because hot Jupiters are big and close enough that they can actually raise a tidal bulge on the stars (and we can actually see the bulge in a handful of cases).

This tidal interaction can cause the planets to spiral downward toward the stars, and at the same time, it causes the spins to spin faster until the planet is destroyed by the star. The same tidal effect, just in reverse, is driving the Moon away from the Earth, while slowing down the Earth’s spin. But here’s the key: we don’t know how quickly the planets are spiraling in.

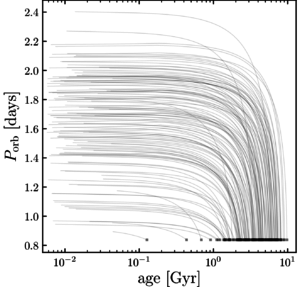

Tidal decay of planetary orbital period over billions of years (Gyrs). From Penev et al. (2018 – https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.05269).

Enter Prof. Kaloyan Penev of UT Dallas Physics Dept. On Valentine’s Day last week, he and his colleagues published an academic love note exploring planetary tidal decay. To do this, they modeled the evolution of planetary orbits and stellar spins under the influence of tides. The tracks in the figure at left show how a planet’s orbital period (or distance from its star) might shrink over billions of years, thanks to tides. The clump of spaghetti noodles in the figure shows that evolution for a range of assumptions about the rate of decay.

By comparing the stellar spin rate and planetary orbit predicted by their model to those we actually observe for each system, Penev and colleagues showed that the tidal decay rates might actually slow down as the planets approach their stars. So perhaps instead of an reckless death dive into the star over a few million years, the planets make like Zeno’s tortoise and tiptoe closer and closer without plunging in.

Upcoming surveys such as the TESS mission and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope may soon allow us to test whether planets do or do not plunge into their stars. Theoretically, we expect stars that eat their planetary children dramatically brighten up by a factor of 10,000 over a few days – faster than a supernova brightens but nowhere near as bright. These surveys might able to see stars engaged in this act of cosmic infanticide.