I really enjoyed a talk from Dr. Josh Bandfield yesterday in the Geosciences Department about unusual geomorphological features on the surface of the Moon.

Bandfield works with the Diviner instrument onboard the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Diviner is a very sensitive camera that measures infrared radiation from the Moon’s surface over a wide range of wavelengths. Using these data, Bandfield and others can learn a surprising amount about the Moon’s surface and geological history.

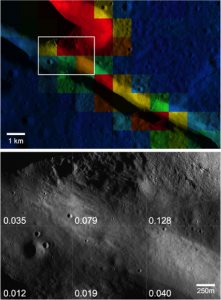

Rock concentration values near Rima Bode (356.1°E, 12.9°N) superposed on a high-res LROC image. The white box denotes the area shown in the bottom image. (bottom) A portion of LROC image. Each square in the image covers a separate Diviner bin with the derived rock concentration value listed.

For example, the rates at which different surface types cool once the Sun sets depend on the surfaces’ thermal conductivity. In general, lunar regolith or soil heats up and cools down much more quickly than bare rock. And so, if Diviner measures a surface’s temperature at a known time of lunar day, Bandfield can determine how rocky the surface is. The figure at left from Bandfield et al. (2011) compares the inferred rockiness of one surface to high-resolution images, which confirm the rockiness map from Diviner data.

Bandfield also discussed how rockiness maps can be used to determine the relative ages of lunar craters. Since the Moon is constantly bombarded by impactors, lunar rocks are continually broken down into finer and finer pieces, finally turning into powdery regolith. By mapping the rockiness of different craters, Bandfield and colleagues found the youngest craters are also the most rocky.

A theme that Bandfield highlighted several times: even though humans have studied the Moon for millenia, it still has fascinating things to reveal.