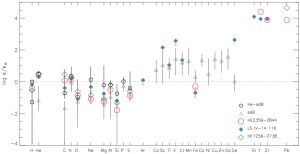

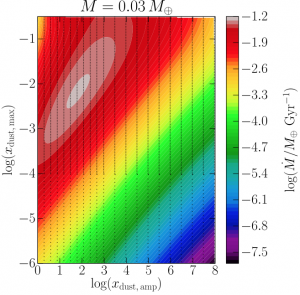

Figure 4 from Perez-Becker & Chiang (2013), showing the how the mass loss rate depends on the amount of dust in the atmosphere (x_dust).

Today in Journal Club, we discussed a paper by Perez-Becker & Chiang (2013).

This paper looked at the mass lost by a rocky extrasolar planet so close to its host star that its surface is melted and a liquid rock lake has formed on the planet’s day side. This work was motivated by Rappaport et al. (2012), which claimed to have discovered a roughly Mercury-sized extrasolar planet candidate orbiting the star KIC 12557548 in data from the Kepler mission. The planet seems to be disintegrating and may disappear in the next few million years.

An atmosphere of rocky vapor likely forms over the liquid rock lake and can actually escape from the planet, owing to the planet’s very low surface gravity. As the gas escapes, it cools (through adiabatic expansion) and can potentially condense into little dust grains, which are then swept out into space by the escaping gas. This putative cloud of dust can help explain some of the observations from Rappaport et al. (2012).

As interesting as the paper is, though, it raises some big questions that we talked about in journal club. For example, the dust should be strongly heated by the starlight and should reach high temperatures (> 2000 K or 3140 degrees F). If the planet’s surface is hot enough that the rocky surface evaporates, why doesn’t the dust also evaporate?

Unfortunately, the star KIC 12557548 is very dim, so it’s hard to observe with other telescopes and learn more about the planet candidate. However, the upcoming TESS mission will probably find more planets like this one, and so we might be able to see other rocky planets that are disintegrating before our eyes.

We also discussed an older paper by Gaudi (2004), which predicts that the Kepler mission might have observed a handful of stellar occultations by Kuiper belt objects (KBOs). During such an occultation, a KBO will block out the light from a background star in a way that depends on its size and how far it is from the Sun. Since Kepler has been staring at about 150,000 stars over 3.5 years, there’s a good chance that a few of those stars were occulted by KBOs. Unfortunately, because Kepler wasn’t designed to look for such signals, it might be very hard to spot them in the data.